The scene of the founding of Guelph on April 23 (St. George’s Day), 1827, has become iconic in local historical lore.

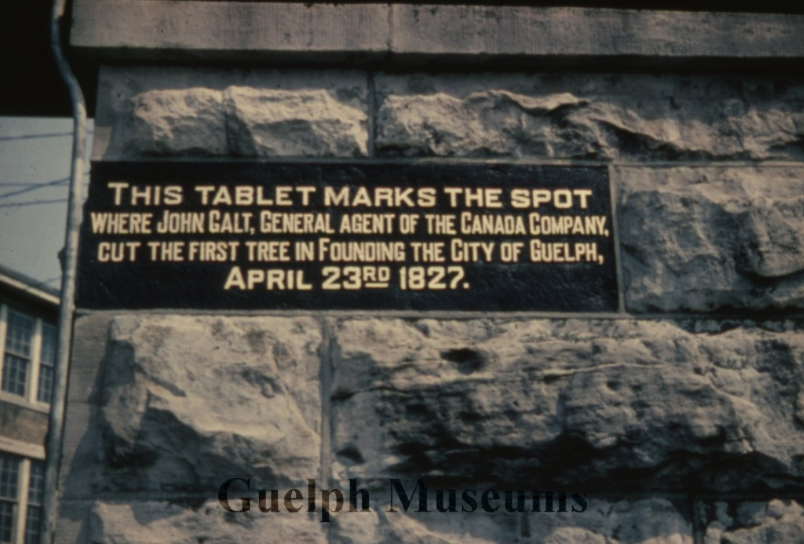

After getting lost in the woods, John Galt and his companion Dr. William “Tiger” Dunlop stood with a small party of men under a large maple tree on the bank of the Speed River, a spot now marked by a plaque. Galt hefted an axe and took the first whack at the tree. Dunlop took the second. Then the accompanying woodsmen did the hard job of cutting the tree down.

There would later be some dispute over who really deserved credit for felling the tree. But let’s focus on that tree, rather than on the people in the picture.

In those days the forest wilderness was seen as a barrier to the march of civilization, so the chopping down of the “first tree” in the founding of a town was significant. Galt wrote of the occasion:

“To me at least the moment was impressive, and the silence of the woods that echoed to the sound was as the sigh of the solemn genius of the wilderness departing forever … The tree fell with a crash of accumulated thunder, as if ancient nature were alarmed at the entrance of social man into her innocent solitudes with his sorrows, his follies, and his crimes. I do not suppose that the solemnity of the occasion was unfelt by the others, for I noticed that after the tree fell, there was a funereal pause as when the coffin is lowered in the grave.”

An eloquent description, but then Galt was, after all, a novelist. But what about that tree? Galt last mentions it as the central part of a simile involving a coffin.

In The Annals of the Town of Guelph (1877), C. Acton Burrows says that after the momentous event, the tree’s stump was planed level and Galt placed a compass on it to serve as a guide for laying out the town’s streets. Later, the four points of the compass were carved into the stump. According to Leo A. Johnson’s History of Guelph (1977), a commemorative sundial was eventually fixed on it. The sundial was called Guelph’s first town clock.

After about 20 years the stump had decayed and was removed to make way for railroad construction. What happened to the rest of the tree? Did it become firewood? There are clues in a letter written in 1943.

In April of that year, Dr. H. O. Howitt, a prominent Guelph citizen, wrote a letter to the Mercury in which he discussed Guelph’s founding. He said that a Miss Davidson, daughter of one of the men with Galt’s party, often expressed to him her annoyance that Galt always got credit for chopping down that first tree. “He only swung the axe once or twice, knocking a few chips off.” She said her father actually did most of the chopping.

Howitt said another man in Galt’s party, a cabinet maker named Baker, used wood from the fallen maple tree to make two oval picture frames and a table. Howitt wrote the table and one of the frames were in his possession, “awaiting the time when Guelph shall have a historical museum.”

Guelph Museums does in fact have a wooden plaque allegedly made from the first tree cut down in Guelph, donated by the late John David Higinbotham. It isn’t oval, but could it have been made from one of those picture frames?

The museum’s administration does not have any information on Howitt’s table, but has expressed interest in it. The story is certainly intriguing. A letter placed in GuelphToday requesting contact with the family of the late Dr. Howitt got a response from relatives. Unfortunately, they didn’t know anything about the table as mentioned in the Mercury letter.

Is that table long gone? Or could it still be somewhere in the community, perhaps in the possession of someone who isn’t aware of its connection to the city’s founding?

One more interesting point in Dr. Howitt’s letter: he said that in 1927, as part of the city’s centennial celebration, a maple tree was planted near the spot where the original tree once stood.

Unfortunately, it failed to take root and had to be removed. Maybe, as Galt wrote, the solemn genius of the wilderness had indeed departed forever.