January of 1946 was an eventful month for Guelph, but not in a way local residents would have wanted. Two disasters marred the early days of the first year without war since 1939.

Two months after a major fire had gutted the Bond Hardware store, the city was still dealing with charges that, although Guelph’s firemen were courageous, the department itself was undermanned and lacking proper equipment. Moreover, insurance underwriters said the city needed a new fire hall, an updated alarm system, and new watermains and fire hydrants.

While Mayor Gordon L. Rife and city council were asking where the money was supposed to come from to pay for all this, fire struck again.

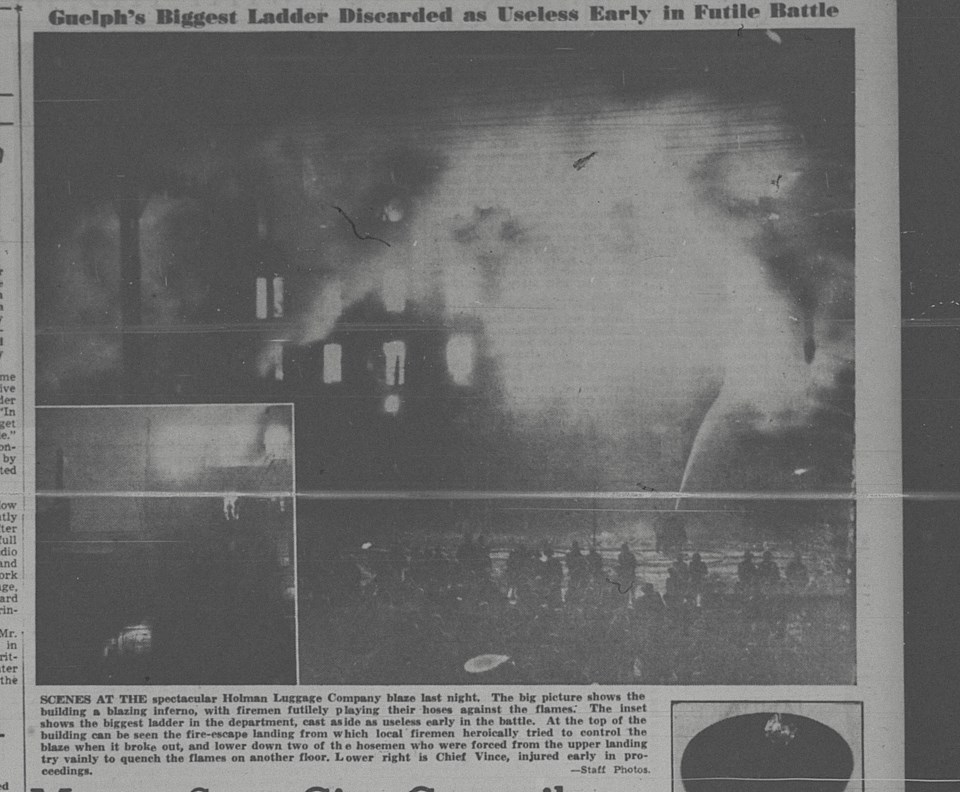

On the evening of Jan. 25, Holman’s Luggage Company on Carden St. went up in flames. The factory, which in addition to luggage made musical instrument cases, radio cabinets and card tables, employed about fifty people, many of whom were returned soldiers. It was housed in an old brick building owned by Ivey Holman.

He told the Mercury the fire had started small on the upper floor, but firemen had been unable to get at it in time to prevent its spread. Spectators who gathered to watch the blaze saw them cast their hoses aside as useless because the water pressure was too low, and one hose leaked. The men also lacked an aerial ladder.

One Mercury reporter wrote, “This writer saw gallant fire fighters, time and time again during the evening, risking their lives in a hopeless task – fighting with the weapons of a child against the power of a Juggernaut.”

The fire spread through the top floor with “hurricane force,” and then crashed through to the floor below.

“From then on,” the reporter continued, “it was only a matter of time, and the firefighters might as well have packed up their kits and returned to the comfort of the fire hall.”

About 30 citizens tried to help the firemen. Hundreds of children, drawn by the spectacle, stood in the snow and watched as though in a trance. Fire Chief Charley Vince was injured battling the inferno and was taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital because Guelph General was filled to capacity. But the only room available in St. Joe’s was in the maternity ward, so Chief Vince was treated in what the newspaper called “The Stork Club.”

Once again, a downtown landmark was destroyed. But the investigation into the costly blaze and an inadequately equipped fire department had barely begun when a new tragedy hit the city.

On the afternoon of Jan. 27, Joseph Lacey, an employee of Standard Brands Ltd., came home after work to find his little house on Edinburgh Road full of gas. His wife, 54-year-old Margaret, lay dead on the bathroom floor. Beside her body was that of their granddaughter, six-year-old Mary.

Lacey found Mary’s sister Marlene, age 8, on a bedroom floor, unconscious but alive.

The girls were the children of the Laceys’ daughter Gladys and her husband Jack Richardson of Fergus. The children had come to Guelph to spend a few days with their grandparents while their parents moved into a new house.

Lacey ran to a neighbour’s house to phone for help. Firemen arrived on the scene quickly. They gave Marlene oxygen and rushed her to St. Joseph’s Hospital where she was placed in an oxygen tent. However, early the next morning the little girl died.

An investigation by police and the fire department showed a gas water heater in the basement had burst at the seams and escaping water had put out the pilot light. The fireman who entered the basement had to wear a gas mask. Upstairs, the lights on two gas stoves had gone out.

Investigators believed Mrs. Lacey and Mary had started to feel ill from the effects of gas and had gone into the bathroom, which was directly over the malfunctioning water heater. There, they had been overcome by fumes.

News of the deaths stunned the city. The funeral held in Fergus for the three victims was one of the largest in the town’s history. Meanwhile, Crown attorney J. M. Kearns immediately ordered an inquest.

The investigation revealed the water heater in the Lacey house had not been installed by a qualified technician and the building was not properly ventilated. Bylaws regulating the use of gas had been passed by city council in 1934, but they were not very well enforced. Numerous warnings had been issued to householders and landlords for such problems as inadequate ventilation.

However, such warnings were usually ignored and there were no penalties for infractions. Landlords argued the cost of installing ventilation was the tenants’ responsibility. The gas company had discontinued service to some customers who had refused to comply with the bylaws, but the municipality had not pursued further consequences.

That was about to change.

The Mercury reported that because of the tragedy on Edinburgh Road, there would be a “drive to end the menace.” Board of Health Sanitary Inspector J. Samuel Tate said bylaws regulating gas would be enforced, and gas would be prohibited to homes without proper ventilation. City engineer H.S. Nicklin said he expected people to comply once they realized the danger. He also stressed the importance of obeying the regulation that said gas appliances had to be installed by qualified people and not “the man of the house.”

The city had learned hard lessons from the downtown fires and the deadly gas leak.