Many people assume Brock Road, which connects Guelph to the 401, was named in honour of War of 1812 hero General Sir Isaac Brock. The road was actually named after Thomas Brock, patriarch of a prominent pioneering Guelph family. Two members of that family were among the Canadians who became involved in a different conflict, and they weren’t the only people with Guelph connections to do so.

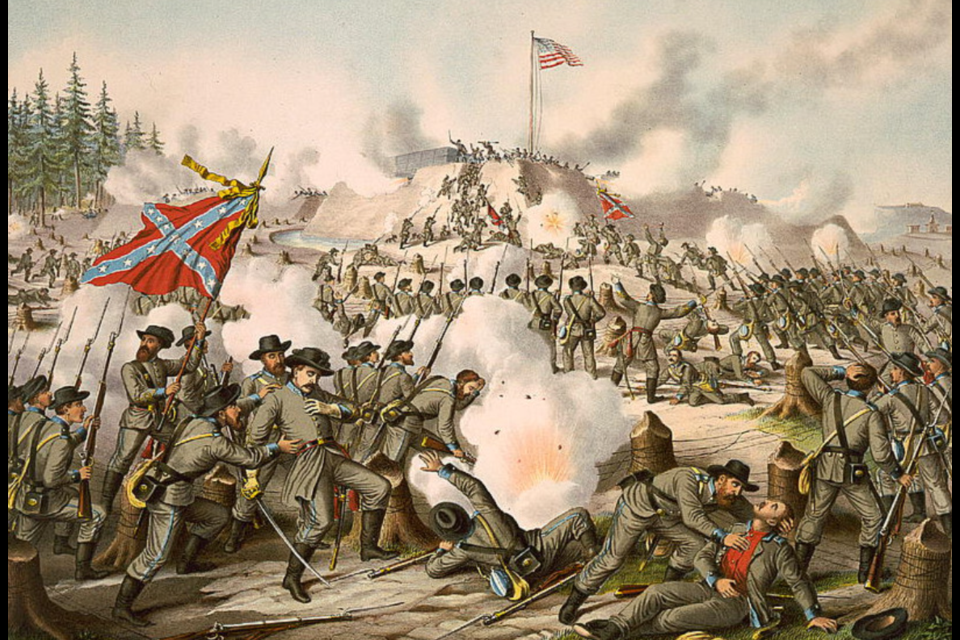

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, thousands of young men in the British colonies that would eventually become Canada decided to head off to fight in a foreign war. Some were attracted by the enlistment bounties being paid to recruits. Others were tricked by “crimps” – conmen who lured naïve youths into uniforms and cheated them out of those bounties. Many were seeking adventure. A few were British soldiers who were bored with garrison duty in colonial Canada.

By far, the greatest number of Canadians who went to fight in the Civil War joined the Union Army. But a few were drawn to the Confederacy. Among them were Thomas Brock’s sons Henry and George.

The Brock brothers were apprentices in business who resided in New York City when the war began. They believed in what the slave-holding southern states considered their “cause,” and in the structured society of the agrarian south. The pair headed for Richmond, Virginia, taking great risk to cross the guarded border that separated north from south.

In the southern capital the two young men met several prominent leaders, including Confederate President Jefferson Davis. They were given the opportunity of joining the cavalry of General J.E.B. Stuart. However, the idea of army discipline didn’t appeal to them. They chose instead to join the 43rd Virginia Partisan Rangers commanded by Col. John S. Mosby, a dashing figure who had earned the nickname “The Grey Ghost of the Confederacy.”

Mosby’s horsemen carried out raids into Union territory, attacking Yankee patrols and supply lines, and terrorizing civilians. Their hit-and-run tactics were very effective. The Brock brothers fought in numerous engagements in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania, and managed to get through the war unscathed.

After the Confederate defeat, the Brocks faced the possibility of prosecution because they had been part of a partisan unit, and the federal government regarded such fighters as being little more than bandits. To avoid arrest they fled to Montreal where they were taken in by an older brother. They eventually returned to the United States where Henry became a friend of President Ulysses S. Grant, the former Union general.

Henry Jackson was among the Canadians who joined the Union army. He was the eldest son of British immigrants Joseph and Mary Jackson who had settled in Guelph Township’s Paisley Block, where Henry was born. He was working in Michigan as an itinerant farm labourer in the summer of 1862 when he decided to enlist. The letters he wrote home show that he was strongly opposed to slavery.

“I wish to impress upon your mind that the war is a war between the government and rebels; not the north against the south as is often expressed. It is a trial between freedom and slavery; not only here but it has its effect over the whole world … I should not have half so much hope of success if I was uncertain that we are right, or in a just cause.”

Jackson fought in the Battle of South Mountain, Maryland, on September 14, 1862. He was wounded in the leg, and was probably in hospital when he learned that following the Union victory at the bloody Battle of Antietam, Virginia, on September 17, President Abraham Lincoln had issued his Emancipation Proclamation, which heralded the end of slavery in the United States.

However, the Proclamation was only words on paper until the Confederacy was defeated. There would be many more battles to fight before that happened. Moreover, not all of Jackson’s comrades-in-arms favoured emancipation, even though they were fighting in Lincoln’s army.

Jackson wrote, “There are a great many Union men … that think the Emancipation Proclamation will not be carried out which seems to me to be more like deliction [sic] than anything else. It is well enough that they should think so at present but they must know that it is an army order and as such must be enforced, although there are a vast [number] of soldiers that are against it.”

Jackson was with General Grant’s army in July of 1863 when it captured Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. That victory, along with Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s defeat at the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg ensured the ultimate demise of the Confederacy.

But the war would drag on to its inevitable conclusion for over a year and a half, and Henry Jackson would not live to see its end. His regiment was part of the Union advance on Knoxville, Tennessee, in the fall of 1863. On November 16, Jackson was shot and killed in a skirmish near a little town called Crab Orchard. A casualty of what he believed to be a just war, the young man from Guelph was buried in an unmarked grave.