On October 10, 1945, federal State Secretary Paul Martin announced that observations held on Nov. 11, which had been the official day to honour Canada’s dead of the Great War since 1919, would now also include the fallen of the Second World War.

That tradition has continued up to the present, and now includes the Canadian dead from the Korean War and other conflicts around the

globe.

Of course, it is right that we remember all those who selflessly made the ultimate sacrifice in times of war. We memorialize their names on cenotaphs like the one in downtown Guelph, and we should always be aware that behind every one of those names there is a story about a real person.

While we honour those who died in service, we should also remember the many who survived harrowing experiences and sometimes made extreme, if not mortal, sacrifices.

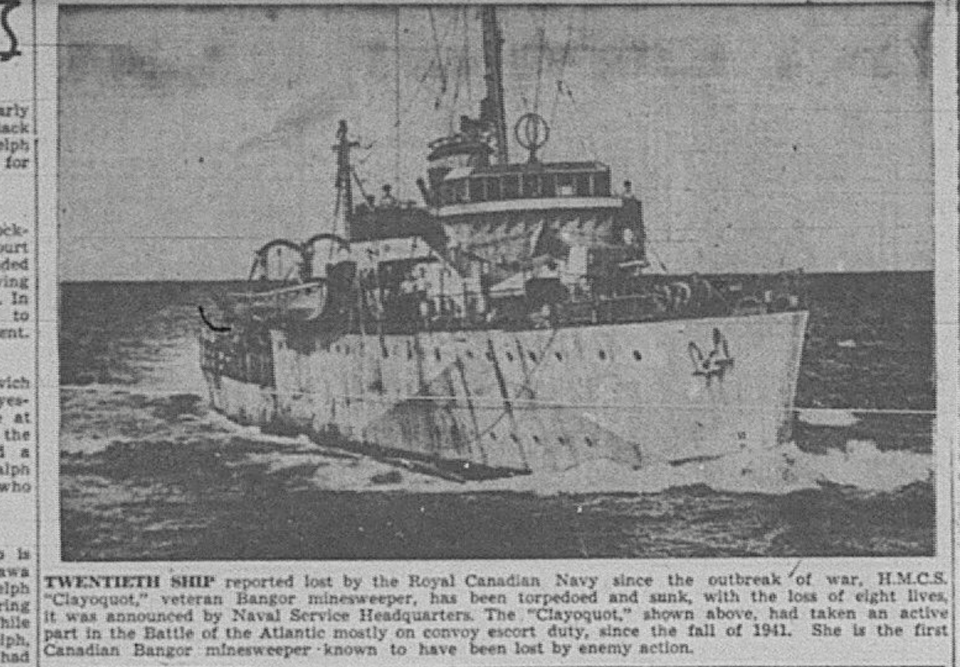

George D. Huck of Kent Streett., formerly a student at St. Stanislaus School and GCVI was a telegraph operator aboard HMCS Clayoquot, a Bangor-class minesweeper. On Christmas Eve, 1944, off Sambro Island, Nova Scotia, the Clayoquot was torpedoed by a German U-boat. The ship sank quickly, with the

loss of eight men. The rest of the crew – 73 men – were rescued by other vessels. The cooks in the galley had to climb onto the stove and escape through a hatch. One of them said, “We got a hot foot, but we broke all records getting out of that galley.”

Another Guelphite on the Clayoquot, leading sick bay attendant Harold G. Elliott, was also among the survivors. George Huck was sent home to Guelph on survivor’s leave, only to wind up in St. Joseph’s Hospital for an appendectomy.

Patricia Bolton, a native of Guelph, was serving as a nurse in England when the hospital to which she’d been posted was bombed. She and the nurse working next to her were thrown against a plate glass window by the force of the blast. The other nurse was killed. Bolton survived, but suffered painful

injuries to her legs that required her to be hospitalized for several months.

While she was recuperating, she met a Canadian soldier whom she married. After the war, she went with him to his home in Winnipeg.

L/Cpl John Rogers of Guelph was a member of the Second Canadian Provost Corps that participated in the raid on Dieppe on Aug. 19, 1942. He was among the many who became prisoners of war, and was sent to PoW camp Stalag 9-C, near Eisenach, Germany.

“They didn’t treat us badly on the whole.” Rogers told the Mercury after the war, “but from October 8, 1942, until November 23, 1943, they kept the Canadians at our camp in chains, because we had tied up German prisoners at Dieppe.”

Rogers, who had four children back in Guelph, spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. For several months he was forced to labour in a salt mine.

Mrs. Gerald Cote of Durham St. in Guelph learned her brother, L/Sgt. Leo Martin of the 43 rd Battery, was taken prisoner three days after the Canadian landing at Juno Beach on D Day. Like other Canadians whose loved ones had been captured by the enemy, Mrs. Cote could do little

except worry about the prisoners’ fate until the war’s end brought about their release.

Once he was back home, Martin told the Mercury German soldiers had taken the Canadians’ watches as “souvenirs.” He said he’d been subjected to mental torture, threats and solitary confinement by interrogators who wanted (but failed to get) information on the Canadian artillery.

Martin reported that Canadian, British and American prisoners were generally treated better than prisoners from Russia and other European countries, and would share their food with them.

Flight Lt. J.D. Golds of Guelph was the navigator aboard a bomber that had just dropped its load of bombs on Remscheid, Germany, when the plane came under attack. He was injured and had to let another crew member take over his station. The plane was hit again, and Golds’ replacement was

killed instantly. Golds and the rest of the crew bailed out. They all parachuted to the ground, but Golds broke his ankle when he landed. The men were all caught by German soldiers and spent the rest of the war in a PoW camp.

WO Joseph J. Lawlor of Guelph was flying with the famed Thunderbird Squadron when his bomber was shot down over Germany in November of 1944. He was captured and sent to a PoW camp where he suffered a broken leg. Not until the following June did his family receive news that he had been freed by Allied forces in April of 1945, but had been in an American military hospital in Paris.

When Flight Lt. Donald A. McIntyre of Clark St. in Guelph was shot down over Germany, he managed to evade capture for three days before German soldiers apprehended him. He was taken to a jail in Frankfurt where he was locked up in solitary confinement for eight days and given only bread

and water. Nazi interrogators threatened him with torture, but he wouldn’t answer their questions.

McIntyre was imprisoned in Stalag 3A until it was liberated by the Soviets. The Red Army kept him for another five weeks before turning him over to the Americans. When McIntyre finally got back to Guelph, he told the Mercury he was “not sorry to be home.”

These are but a small number of the stories men and women of Guelph brought back from the war. On Nov. 11, we do well to remember all of those who accepted duty and responsibility, and did their part.