On a November day in 1906, a young man named William Alexander Moir suffered a “fit” at Guelph’s Albion Hotel, where he’d been boarding.

He was taken in a comatose state to the hospital where he was attended to by three doctors, including Dr. W.J. Robinson of the Homewood Sanitarium. Moir’s friend, James Miller, said that the stricken man had been a victim of sunstroke while serving with the British Army in South Africa. However, Dr. Robinson believed Moir had epilepsy, a little-understood disease at that time, and thought the seizure had been triggered by alcohol.

When Moir was sufficiently recovered, Miller got him a room at the boarding house on Waterloo Avenue where he resided, feeling his friend would be better off away from the temptation of the Albion’s bar. He knew Moir to be a “decent chap,” usually easy-going, except when he drank too much. At those times he could be bad-tempered, and on at least one occasion had threatened the bartender.

Moir was from Scotland. After being discharged from the army he’d immigrated to Canada in 1905. It’s uncertain exactly when he arrived in Guelph, but he made a lot of friends. People tended to forgive him those Jekyll and Hyde episodes that occurred when he had a few drinks.

Then came the fateful day when William Moir became the most wanted man in Canada.

Moir suffered another “fit” in March, 1907. Perhaps he had a difficult time holding a job, because sometime later he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Regiment. Native-born Canadians hadn’t shown much enthusiasm for joining the army, so the regiment was always willing to accept British veterans. Moir was stationed at Wolseley Barracks in London, Ontario.

On evenings that he had leave, he would go to a bar in town. Once again, Moir gained a reputation for being argumentative when he was drinking. He was also suspected of eating cordite, a substance used in ammunition that had a narcotic effect if ingested. This wasn’t an uncommon habit among soldiers.

On the night of April 17, 1908, Lieutenant F.D. Snider saw Moir return to the barracks from an evening out. Moir was wearing military ribbons that were considered improper dress for town. The officer told Colour-Sergeant Henry Lloyd to look into the matter. Lloyd confronted Moir and told him he would be placed on report the next day. Lloyd then left the room.

Moir went to his quarters in a rage. He armed himself with two revolvers and a rifle. Then he went to a basement room and began to raise a ruckus, even firing one of the pistols. The racket brought Lieutenant George Morris and Lloyd to the scene. When they entered the room, Moir had the rifle in his hands. Lloyd said, “Put that gun down.”

Moir didn’t obey, and Morris told Lloyd, “Take that gun away from him.” Lloyd advanced on Moir, who shot him at point-blank range. Sergeant Lloyd, age 25, died within an hour.

Moir fled with his guns and a large supply of ammunition. As newspapers carried the shocking story of Sergeant Lloyd’s murder, the fugitive disappeared into the countryside.

The public read daily reports of the manhunt. It was said that because of his military experience in Africa, Moir knew how to survive in the bush.

Police had orders to bring Moir in dead or alive. They hunted for him all over Southern Ontario: London, Stratford, Guelph, Seaforth, Goderich. Many people believed he had fled to the United States. A $500 reward was offered for information leading to his capture.

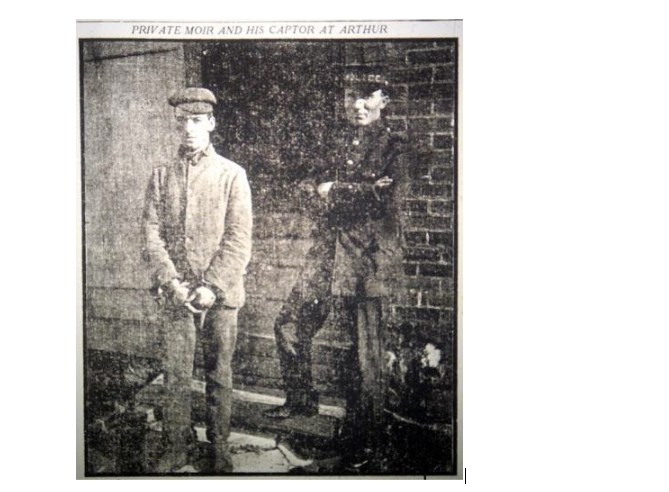

On May 10, Guelph Police Chief Frederick Randall received a tip that Moir was working at a farm near Elora. He headed for Elora with a party of constables, but arrived too late. Moir had already been arrested by a pair of constables from Arthur. They’d taken him by surprise when he was unarmed, and subdued him after a desperate fight. The farmer hadn’t known the drifter he’d hired was a wanted man.

Even though Moir was charged with murder, for which he could hang, he had many sympathizers, especially in Guelph. They believed his claim that he had no memory of shooting Lloyd or anything that followed, aside from waking up one morning in a strange barn. Investigation showed there was a history of mental illness in his family. Moreover, people said he just didn’t look like a fellow who would deliberately kill anybody. Moir’s Guelph friends began a subscription to raise funds for his legal defence.

Moir went to trial in London in January 1909. There was no doubt that he’d shot Lloyd. The question concerned whether or not he was sane at the time. Several experts in the field of mental illness, including doctors from the Homewood, testified that Moir was epileptic. They said he wasn’t responsible for things he did while in the grip of a “fit.”

The jury found Moir not guilty by reason of insanity. He wouldn’t hang, but he was committed to life in a mental institution in Hamilton.

In August 1910, Moir escaped from the asylum. Once again, the search was on. Police scoured the countryside from Toronto to Niagara Falls, paying particular attention to Guelph and vicinity. A week after the break-out, he was apprehended on a farm near St. David’s. This time he was locked up in Toronto’s Central Prison.

Moir might have remained in jail for life, but he was a model prisoner and became friendly with a Salvation Army brigadier who visited him regularly. When the First World War broke out, Moir said he wished to make up for past deeds by re-joining the British Army. Doctors decided that he was no longer insane and the provincial government agreed to his release on the condition that the Salvation Army officer accompany him to Halifax and see him board a ship for England.

Moir was killed in France in 1917. He is remembered as a war hero in his hometown of Hawick, Scotland. Not so in his one-time home of Guelph.