It is unlikely the hummingbird that got its beak stuck in the screen door at Nicholas and Cheryl Ruddock’s cottage four years ago was named Zephyrax, but his fleeting error of aeronautical navigation made a lasting impression.

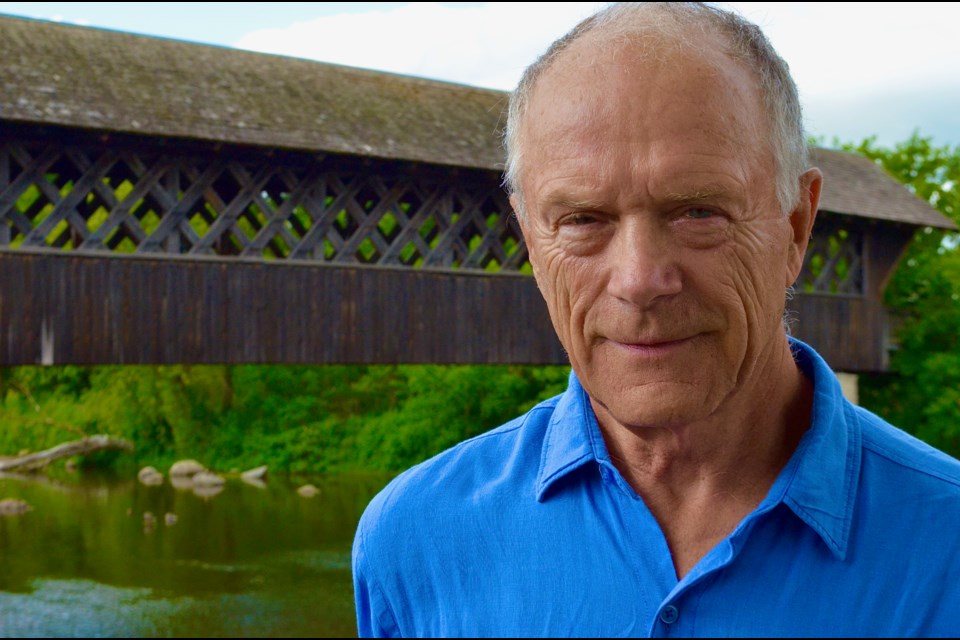

In fact, he inspired the creation of a highly articulate hummingbird that goes by that very name, as well as a virtual menagerie of equally articulate protagonists that populate the pages of Nicholas Ruddock’s new adventure novel, The Last Hummingbird West of Chile.

“When I started to write about the hummingbird, I realized that the hummingbird was going to have to talk and once the hummingbird started to talk it hardly made any sense to have other objects not have a voice,” said Ruddock. “Really, that became the overriding theme.”

The narrative flows seamlessly between the lives and first-person observations of people living in the early 1800s, such as 16-year-old chambermaid and murder accomplice, Clovis Oldham, and less traditional literary characters such as a wise 250-year-old white oak named Quercus Alba.

“Certainly, there is a lot of information out now about trees and how they actually do talk,” said Ruddock. “They have lives. They communicate through the ground and through pollen and somehow, I managed to get in on the ground floor with that by having my tree do all of those things before it became common knowledge.”

It is Ruddock’s inclusion of these typically overlooked voices that breathes new life into a classic and beloved form of epic tale telling.

“There are so many voices around us that we don’t hear, or we no longer hear and by giving them a voice it changed the whole novel from being a mere adventure story to being an adventure story with multiple characters, all invested in it,” said Ruddock. “How important it is to realize that trees, and stones for that matter, I mean everything around us, is alive.”

The equity of voices, whether they be donkeys, pigs, people or a coral reef, is achieved by giving every character equal command of a common language.

“I think I have somewhere between 25 and 30 characters, including animals and birds and inanimate objects,” said Ruddock. “If I were to try to write for them each in separate voices it would end up being cartoonish. So, I chose to have them all speak in English, fairly sophisticated English, and let the substance of what they were saying form their character.”

Of course, it is Ruddock’s gifted command of language, wit and wild imagination that suspends all disbelief and takes readers on a fantastic voyage, often through dark scenes and controversial themes.

The story is anchored in the 19th century and written in a literary style reminiscent of Swift, Melville and other classic adventure writers of that era but provides telescopic hindsight on contemporary issues such as environmental exploitation, poverty, racism, sexual abuse, the spread of infectious disease and the enduring impact of colonialism.

“I know, and boldly, I have entered into that fray,” said Ruddock. “Since it is set in 1852, it does deal in the colonial times. It deals with subjects that are now pretty touchy such as first contact and love affairs between races.”

He was cautious not to offend modern sensibilities without compromising the story.

“In the writing process there were several times that I was called to task either by my wife or my editors at Breakwater to be careful,” he said. “Although it describes what life was like back there, I think the outlook on it is quite modern and sensitive to that.”

Perhaps it is out of an abundance of caution that Ruddock doesn’t typically use personal experiences as a source for characters and storylines in his books but not even the best editor can prevent history from repeating itself or art from imitating life.

He began writing the novel four years ago, shortly after retiring from a 40-year career as a physician and nearly three years before the global COVID 19 pandemic.

“I didn’t know the pandemic was happening but there is a scene involving tuberculosis with Indigenous people being more susceptible to it,” he said. “I won’t give away the whole thing, but the tree is involved. I will say that. The tree can’t get tuberculosis, but the tree can have great sympathy for those who have.”

He does allow for some personal experience to work its way into his award-winning poetry and a good recent example of that can be seen in his collaboration with local singer-songwriter Shannon Kingsbury.

“She has done a beautiful video of it,” said Ruddock. “It’s called River Eramosa. It’s my first crack at a song.”

The song is one of five finalists in the 2Rivers Festival, Tributary to the Rivers song-writing contest with the winner being announced Saturday, June 26, during an online event starting at 7 p.m.

The Last Hummingbird West of Chile is set for release by Breakwater Books before the end of the month but here is a short video to get some flavour of the narrative.

Ruddock considers it his best work to date.

“To be honest, I didn’t really know what I was doing for the first couple books,” he said. “They all came out and they did okay but this one I feel closer to. I am invested in the characters themselves and I would be pleased if people came to love the characters as much as I do. There are three or four or five of them, or maybe even more that are quite charming or idiosyncratic.”

Perhaps some thanks should go as well to the hummingbird Zephyrax, or whatever his real name is, for disrupting the relative calm of retirement at the Ruddock family cottage all those years ago and opening the proverbial door to an epic adventure.

“The hummingbird comes out as the most interesting character to most people who read it because the hummingbird has a huge role in the book,” said Ruddock. “We gently pushed on the tip of his beak until he was free and then he flew back and forth furiously. They are furious little creatures.”