Shortly before 8 p.m. on July 22, 2000, Guelph Police Service dispatcher Trevor Harness received an urgent 911 call.

“I was just biking the path near the Manor,” said the caller. “There was a kid crying and I guess someone is hurting him, I don’t know.”

Harness pressed the caller to explain why he believed someone was hurting a child.

“Like, someone is cuz I heard rocks throwing,” the caller responded. “I heard a kid crying and his father said, ‘Why did you do this?’ and I heard a brick fell.”

Three constables were sent to the corner of Eden Place and Silvercreek Parkway South to search an old gravel quarry, known locally as The Pits.

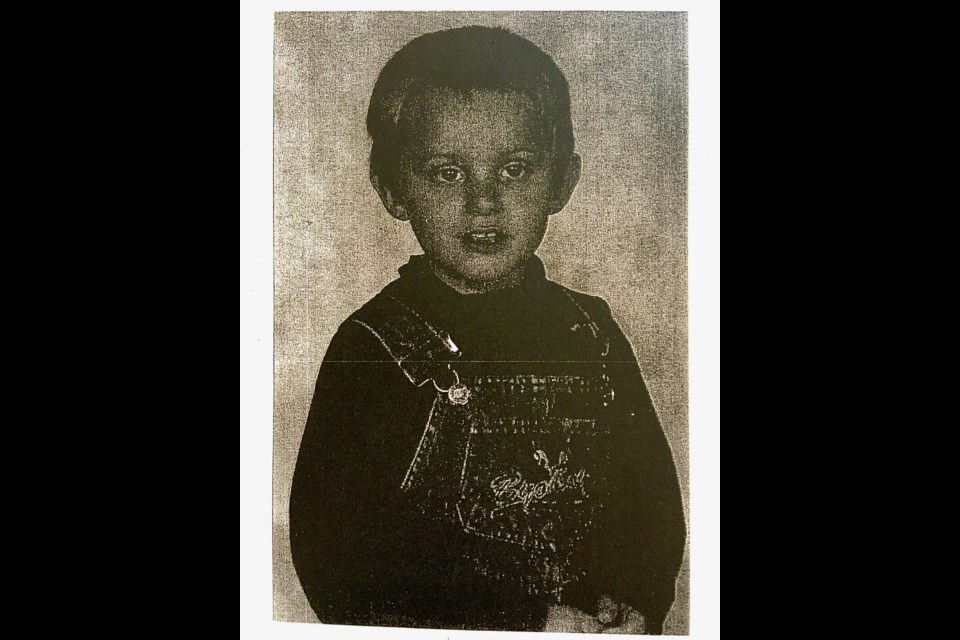

Shortly after they arrived, they were approached by a woman, Anna Kuzyk, who said her four-year-old son David had been missing for nearly an hour.

They searched for about half an hour before asking the 911 caller to come to the location.

The caller, 15-year-old, Richard Behm arrived, eager to help, and pointed the constables to the area where he said he heard a child crying.

He was then told to go home, and police would call if they needed him. Behm would call police two more times to offer his assistance.

By 9 p.m. several more officers had joined the search that had expanded to surrounding neighbourhoods.

A canine unit from the Waterloo Region Police Service arrived as well as members of the Guelph Fire Department who set up search lights.

A neighbour told police she saw David with a teenage boy around 7:45 p.m.

Someone had pulled the fire alarm in their apartment building and the boy, who had a “speech impediment," told her to call the fire department.

They sent an officer to pick up Behm around 10 p.m. and when he arrived the neighbour identified him as the teenager she saw with David.

Behm told police they were searching in the wrong area and pointed to a gully roughly 40 metres from the entrance to the quarry.

Within minutes, a firefighter found David lying in a pile of construction debris. He was bleeding heavily from a headwound and moaning. There was blood on the ground and on a nearby cinder block. He was rushed to Guelph General Hospital and later transferred to Hamilton Health Services Department of Critical Care.

Behm was charged, at the scene, with attempted murder and the next day an additional charge of aggravated assault was added.

He was denied bail and would spend the next 10 months in custody, partly for his own safety. His protections under the Young Offenders Act were waived and a publication ban was lifted when the case was transferred to adult court.

“I was watching CNN and my name was posted,” said Behm, discussing the case over 20 years later in an interview with GuelphToday. “I was like, ’What the hell. I’m a young offender.’ After that it was a landslide. After that everyone knew who it was.”

The story made international headlines and ignited outrage and fear in the community. The Behm family became targets of some people’s anger.

“Every day I went to work people would leave newspapers at my desk,” said Ernie Behm, Richard’s father. “It was very stressful for my mother who had cancer. My daughter was getting bullied at school and she even got death threats.”

David Kuzyk spent 10 days in the critical care unit where he underwent surgeries to repair his fractured skull and reduce swelling of his brain. He was covered in bruises and abrasions that one medical expert testified were consistent with someone who had been thrown from a moving vehicle.

David was unable to identify Behm from a photo lineup but had recovered sufficiently to testify against him during the trial in May of 2001.

Forensic and eyewitness evidence placed Behm with David at the time of his injuries, but Behm denied any involvement and stuck to his initial story for months.

“I was a scared kid and I was lost,” said Behm. “I didn’t think anyone would believe me. I was so traumatized that at one point I was put on a suicide watch.”

He had no criminal record but was known to police as a troubled child who had a history of making up stories when he got in trouble. He had mild autism and was developmentally delayed, partly due to a childhood illness. He functioned at a level years below his actual age and his behavioural problems increased when his parents divorced and his mother remarried.

The police had a challenging case to solve with their only witnesses being a four-year-old child with a brain injury and the accused, a 15-year-old with a mental disability, a proclivity for lying and no clear motive.

Their theory was that Behm had left his home in a blind rage after an argument with his father and rode his bike to the apartment building near David Kuzyk’s home. They believed he pulled the fire alarm to lure David to a secluded area in the gravel pit where he savagely beat him and smashed his head in with a cinder block.

It would later come out that mischievous neighbourhood children pulled the fire alarm as often as twice a week and it may have been David who pulled it that day.

By the time of the trial Behm had retained a new lawyer and was prepared to tell the court what he maintains really happened

He testified that it had all been a careless accident. He was playing with David and attempted to give him an airplane ride by holding his legs and swinging him around. David’s head struck a cinder block and his body twisted around causing Behm to lose his grip. David was flung into a pile of construction debris where he lay semi-conscious for more than two hours.

Behm panicked and raced home to make the fateful 911 call. Ironically, he said he made up the assault story so he wouldn’t get into trouble.

Testimony by David that the he was playing with the “bad guy” and that he was “holding me by my knees upside down” and swinging him around appeared to corroborate with Behm’s account.

It took the jury four hours to return with a verdict of not guilty on both charges.

“I felt great to be acquitted but then I had to deal with people thinking I got away with it because I lied,” said Behm.

The stigma stayed with him for years and even some of his friends and family shunned him. He quit school because he was being bullied and was diagnosed with depression.

In 2013 he met a woman online and they were married a year later. He took her last name and moved to another city where he could start a new life.

David Kuzyk is 25 now and his memories of the incident are foggy.

His mother told reporters at the end of trial that she didn’t believe Behm’s story and was disappointed with the verdict.

“I’m not sure what to believe,” said Kuzyk. “Even if it was an accident, it is something that impacted me. If you lie eventually that lie will come back and bite you in the butt.”

The injury has affected his short-term and long-term memory.

“I remember asking Richard to play with me and holding his hand as we walked over the tracks, but I have no memory of what happened after that,” he said. “With that part of the brain at that age it is nearly impossible to fully recover.”

He suffered from severe headaches for more than 10 years and struggled to keep up in school because he was two years behind kids his age. Before the accident he spoke Polish and English fluently and he worked with a speech therapist to restore his vocabulary.

“I was bullied in school because of my learning disabilities,” he said. “Kids called me scar face, Frankenstein and retard. As a result, I had low self-esteem and felt I had to work hard to prove myself.”

In 2019 he graduated from Acadia University with a bachelor of science degree in geology and is hoping to find work locally so he can stay close to family and friends.

He doesn’t think about what happened too often but believes Behm should have got psychological help rather than being charged and tried in adult court.

“He didn’t really attempt to kill me or else he wouldn’t have called for help,” said Kuzyk. “I am still alive because that phone call was given, and it is a relief to my parents that I am still alive. I have moved forward with my life and I wish he would too. As long as he tries to be a better person then that is fine with me.”