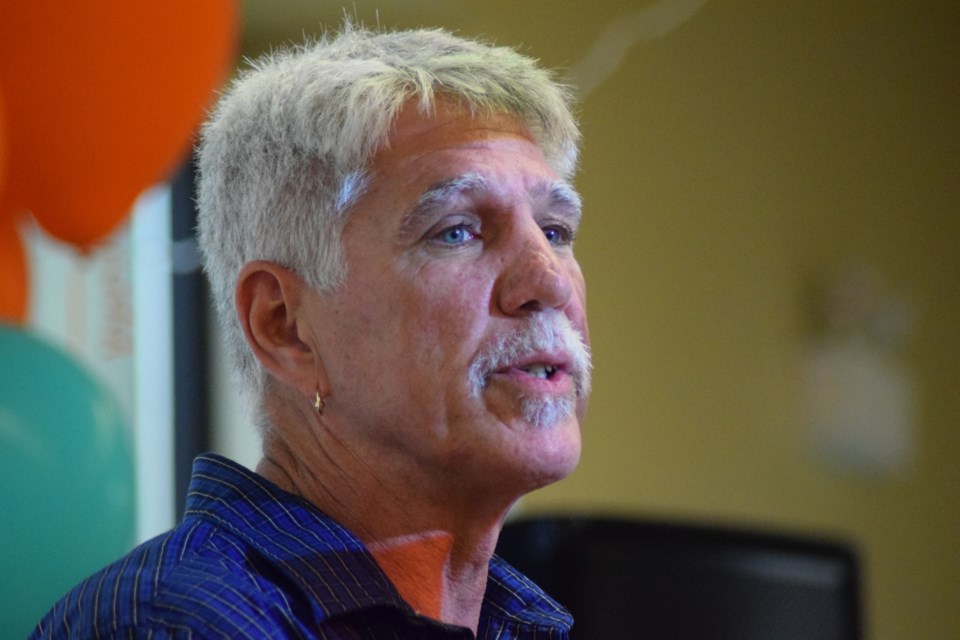

There’s a synergy in life that happens when you make a move in the right direction, Rick Osborne told a captivated audience Monday night at the annual general meeting of Family Counselling and Support Services for Guelph Wellington.

The organization is 30-years-old this year. That’s about how long Osborne, a biker gang enforcer, spent behind maximum security bars.

That “right direction” for Osborne was not taking a lethal dose of black tar heroin to kill himself, instead of being killed in prison. His choice meant he would almost certainly be murdered, but at least he would not die a junkie.

Osborne’s story is about as harsh, violent and self-destructive as they come, and yet all in the audience could see the undeniable innocence in him, and could empathize with the horrible circumstances that turned his life into a living hell.

As a 14-year-old boy he was bullied for defending girls against harassment at his new school in Niagara Falls. He became sullen and withdrawn, avoiding others, riding his dirt bike until the sun went down and he felt safe enough to go home.

In around 1970 he became enamoured with a cool guy with a cool car and started hanging around him. That guy gave him a ride in his cool car, took him to a hotel room where another man was waiting with syringes, spoons and baggies of heroin and cocaine.

One of the men injected Rick against his will with a potent speedball, a combination of heroin and cocaine, that should have killed him. He survived, but just like that he was a heroin addict.

“That’s how quickly I was a heroin addict,” he said. “Just like that I started chasing the dragon.” He was 15.

That first year as an addict was a nightmare. He left home, and ended up on the streets in Florida. He overdosed twice. He got shot once. He was raped, beaten and left for dead by the kind of violent sex offender that, he said, convicts in prison are happy to kill. He underwent electroshock therapy for drug addiction. It didn’t work.

His father found him and arranged his son’s transport home, but Rick was too ashamed to stay. He left again, and stayed gone.

He lived a life that was barely survivable. He started robbing drug dealers for drugs, an activity that is nearly always a death sentence. He robbed from the members of an outlaw biker gang, and that surely should have got him killed.

“If you want to have a good life, don’t rob a biker,” he said.

But the head of the gang saw something in him that he liked, and he was taken in. Right away Osborne became part of a “wrecking crew” – a team of ruthless robbers that rob other criminals. He carried three guns, wore a bulletproof vest, and had a life expectancy of five years. But before death caught up to him he was sent to prison – 31 years for gangsterism.

On his first night in prison, the biggest rat he had ever seen crawled out of his toilet, shook itself off and sniffed around his three-by-three feet cell for something to eat.

In Osborne’s audience at Monday night’s meeting was a 13-year-old boy named Dylan Stillaway. Before Osborne spoke, Stillaway addressed the audience. He was there with his mom.

Dylan came from a rough home and it gave him an edge. He became angry, and started acting out and getting in trouble. Then he found Family Counselling and Support Services’ pilot program Peaceful Alternatives for Male Youth at Risk.

The program, Dylan said, taught him to talk about his feelings, and helped him “get through the day without getting angry.”

“It got easier to talk,” the boy said. “I was less depressed and happier.” His story brought many to tears.

Osborne’s arms are blackened with layer upon layer of tattoos. But if you look closely at his arms, he said, you can see the cuttings. He started self-mutilating soon after starting heroin, cutting himself with a razor blade to dull the emotional pain he felt.

The decision not to kill himself opened a synergistic door. A highly persuasive lawyer talked the warden at the Kingston Penitentiary into sending Osborne to a drug rehabilitation facility in Sault Ste. Marie. He returned to Kingston a year later, clean. He stopped doing drugs.

“I love life now,” he said. “I’m not a junkie.” He never cut himself again, and never did drugs again.

An attention deficit kid who could barely read, he learned to love reading in prison. Out of prison he went to school and became an addiction councillor. He wrote the book White Noise, about his harsh life. He spends much of his time talking to at-risk kids, telling them his story and giving them time to ask any questions they want to.

The best thing you can teach a kid, he told the audience, is resiliency.