The opioid crisis is no more, not that it was adequately addressed.

Rather it has evolved into a wider “drug poisoning crisis,” contends Adrienne Crowder, Guelph Wellington Drug Strategy (GWDS) manager.

It’s nothing new that incidents of overdose often involve more than one substance, such as opioids mixed with stimulants like cocaine or other depressants like benzodiazepines, though the problem has become more apparent during the pandemic, as has society’s willingness to change … in some circumstances.

“The substances that put people at risk … they’re multiple, it’s not solely opioids,” Crowder said. “Very few people are getting pure anything. Because the drugs are sold on the unregulated market, people don’t actually know what they’re getting.”

Nearly 2,500 people died throughout the province last year due to drug overdoses, the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network (ODPRN) reports. There were 24 fatal overdoses in Guelph and Wellington County, up from seven in 2019, based on data from Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health as reviewed and presented by GWDS.

“Fentanyl has become very common on the unregulated drug market. It’s pushed out a lot of other substances,” Crowder said, noting that because of its relatively small size, it’s easier to smuggle into the country, especially with the land borders closed during the pandemic. “Small amounts translate into large amounts of money by the time you cut it and market it.”

Of the provincial overdose deaths noted by ODPRN, fentanyl contributed to 87 per cent, with stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamines playing a role in 58 per cent, and the presence of benzodiazepines factored into 46 per cent.

One-in-six were people experiencing homelessness and about 30 per cent of employed people worked in the construction industry.

While there’s no local data to confirm it, Crowder believes those provincial figures generally hold true in Guelph and Wellington County.

“It is likely that the situation in Guelph Wellington reflects the stats … since the risk factors that underlie substance use are relatively universal,” she said.

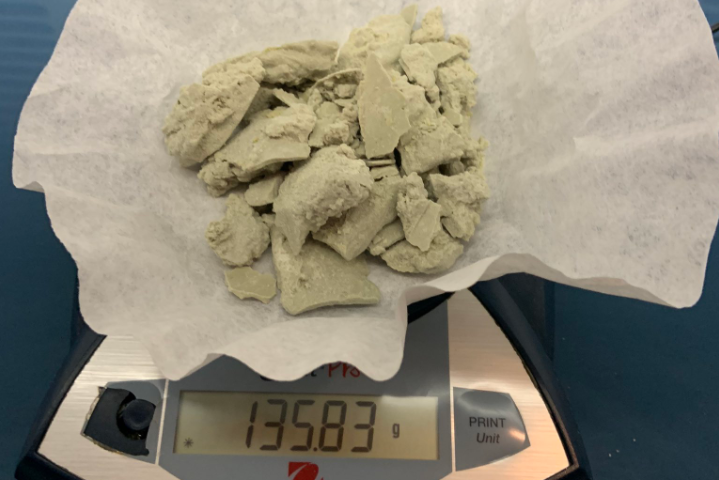

During the past five years, fentanyl seizures by Guelph Police Service have gone up nearly six-fold, from 23.8 grams in 2015 to 1,126 grams last year, which was nearly double the amount confiscated during 2019, confirmed Sgt. Brad Saint of the drug unit.

“The spike in fentanyl seizures is attributed to the prevalence of the substance in our community,” he said via email, noting investigations led to several large seizures last year, the largest of which involved 275 grams and saw two men charged with possession for the purpose of trafficking.

Criminalization of small quantities of drugs is part of the problem, Crowder said when asked how the problem can be addressed, calling for a multi-tiered approach similar to how other health problems are approached.

“There are a lot of good solutions. The challenge is changing social and health policy to allow those solutions to come into play,” she said, listing decriminalization of personal use quantities of drugs, increased resources for harm reduction and treatment options, as well as preventative and support programs intended to help people seeking illegal drugs to find healthier ways of coping with challenges in their life.

“We are sending people who have a health challenge, on a daily basis, to an unregulated drug market that has no quality control. That’s a policy decision that, as a culture, we are making right now,” Crowder said. “If we said to every third person who has diabetes, ‘I’m sorry, we just don’t have capacity to treat you,’ we wouldn’t do that. But we do that with people who have addiction.

“It’s very hard to watch.”

The drug poisoning crisis was created by the health care system that fails to get at the root causes of drug use, she said, noting system changes needed to address the issue are happening “slowly and they don’t happen proportional to the problem.”

“When I watch how policy has been changed to manage the virus of COVID and how quickly that can change, it can be quite a challenge to watch how it has not changed for challenges around the drug-poisoning crisis because the drug-poisoning crisis is actually caused by social policy whereas a virus is not caused by social policy,” Crowder explained.

“It’s an interesting and, for someone from my perspective, a very good process to try to start dealing with the complications of a health issue through health programming.”