The Priory was the first substantial building erected in Guelph and for nearly a century it stood on the western bank of the Speed River, a literal stone’s throw from the stump of the first tree felled by Canada Company representative John Galt when he founded the settlement of Guelph in 1827.

It would be difficult to identify a building more symbolic of Guelph’s origin story but, due to years of neglect, followed by delayed and inadequate restoration efforts, the Priory’s ultimate fate failed to reflect its historical and cultural significance.

“I think it is a recurring theme everywhere, with few exceptions,” said historian Cameron Shelley. “Normally, restoration efforts don’t get much traction until the last moment when something is about to go and that was the case with the Priory.”

Shelley is a researcher and lecturer in the Department of Systems Design Engineering at the University of Waterloo.

He has done extensive research into the history of Guelph and in 2017 published an article for the Guelph Historical Society entitled, The Fate of the Priory.

“It’s nice to understand why things are the way they are and that requires knowing how they were,” said Shelley. “I teach a class at Waterloo called Technology, Society and the Modern City and a lot of the students are very involved in things as they are now. They want to innovate and do things differently and a lot of the class is about how things got to be the way they are already, and it is an eye opener for them and for me. I always learn new things.”

The word prior has its origins in Latin and refers to an elder or superior, quite often a cleric. It is more commonly used these days to describe something that came before. A priory was a religious house or sanctuary typically governed by a prior.

It seems a fitting title for our city’s first home and civic centre but in fact The Priory was named after a Canada Company builder, Charles Prior who oversaw its construction.

It sat on a rectangular, 1.6-hectare lot that spanned both sides of the Speed River starting at, what is today the bus platform on Macdonell Street and west to Arthur Street then north along the river on both sides to Douglas Street.

The front entrance looked out over the river and was located where the, Time Line/Water Line Sculpture, by Hillside sculptor John McEwen now stands in John Galt Park.

The Priory served as John Galt’s stately home, as a civic centre and as Guelph’s first post office, as well as the living quarters for other executives of the Canada Company until 1929 when Galt was recalled to England.

It was then sold and became the private residence for a successive list of prominent Guelphites including nearby mill owners David Allan and David Spence.

The building as well as the manicured grounds, greenhouse and gardens were designed to impress and even earned lavish praise from political activist and journalist William Lyon MacKenzie who visited in 1831 and described it as “fitted for a prince."

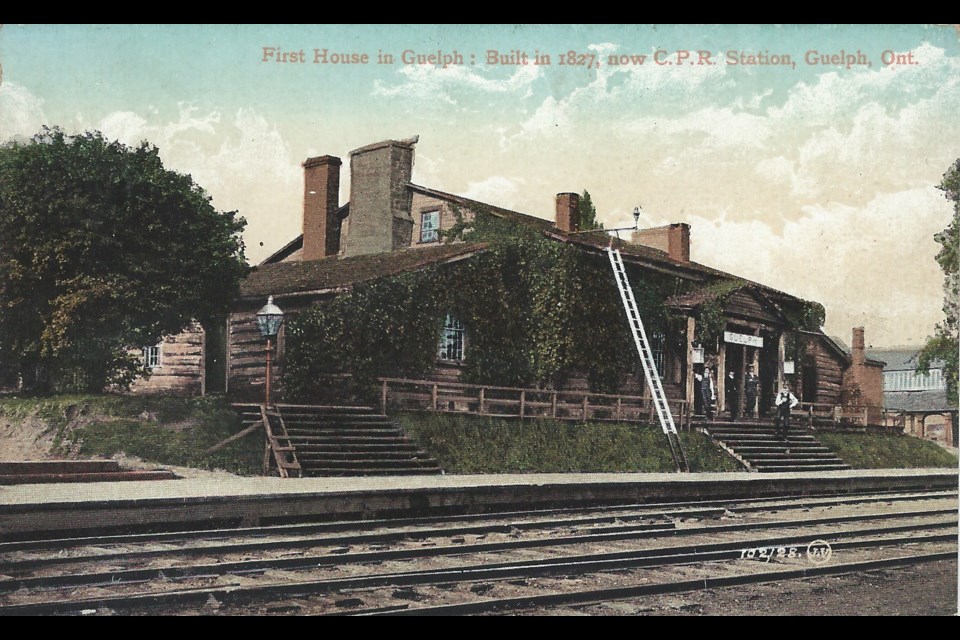

It remained a private residence until 1888 when Spence sold it to the city and the newly establish Guelph Junction Railway. It was then converted to a passenger train station and leased along with the rail line to the Canadian Pacific Railway. The greenhouse and gardens were replaced with storage sheds and the maintenance and care for the Priory was dramatically reduced.

That, historians agree, marked the beginning of The Priory’s steady decline or what Shelley described as “demolition by neglect”.

By1904 the voices of progress were the loudest and the CPR was demanding the city tear down the Priory and build a new, modern brick and stone passenger station more fitting of a growing city at the dawn of a new century.

There were some who wanted to preserve the historic landmark by moving it to Exhibition Park and turning it into a museum, but municipal council wouldn’t pay the $500 needed to move it. Former Mayor George Sleeman bought it in 1911 and moved the north and south wings of the building to his property on Waterloo Avenue. This effort, though well-intended, only hastened the decline of the structure. By 1922 it had caught on fire three times, arson was suspected, and it was barely standing.

In 1924 plans were made to build a Priory memorial using logs salvaged from the dilapidated structure but those plans failed to materialize and in 1926 it was condemned.

On May 4, 1926 roughly 11 months before its 100th birthday and Guelph’s centennial, The Priory was demolished. The order was given with the provision that a 24 x 20-foot scale model be erected in Riverside Park as part of the city’s centennial celebrations using salvaged materials from The Priory.

However, the $2,200 price tag proved too high for a newly-elected city council and instead a miniature scale model was made and placed on a float that was pulled through the city during the centennial parade. That model now stands on a hill near the entrance to Riverside Park.

There was talk in the 1950s of using what was left of the wings George Sleeman had salvaged in 1911 to build a replica of the Priory for the new Doon Pioneer Village in Kitchener but those plans fell through and the logs were allowed to rot. Fire and rot were the fate of the other materials as well.

Shelley’s article on The Fate of the Priory offers a fascinating look at the growth of Guelph and its changing priorities using quotes and observations lifted from contemporary newspapers and documents from each era. It is easy to look back through a lens of historical reverence and preservation, and question why there weren’t more concerted efforts to preserve The Priory but are our priorities all that different today?

“I was intrigued and still am about why some things get preserved and others don’t,” said Shelley. “People looked at the Priory and saw something old and decrepit. It had not been kept up. It was past its best-before date. They had removed all the things that made it nice. They removed the gardens and put up a bunch of sheds and it became a utility building. We are always facing a similar sort of dilemma with things that are around already, things you want to change. How do you reconcile plans for the future with plans that people had in the past?”

Shelley's full account of The Fate of the Priory can be found here.