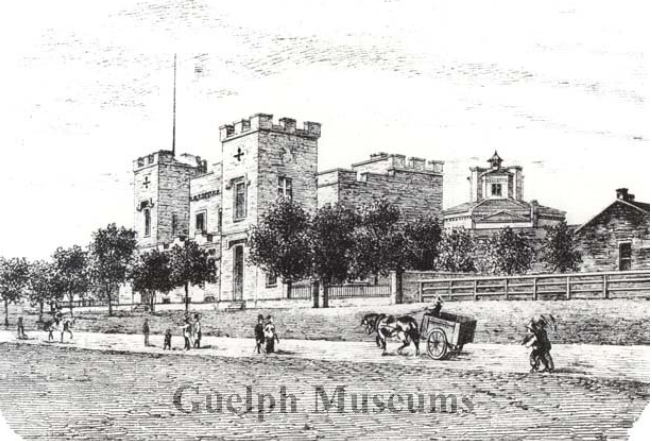

The Wellington County Courthouse and Jail (or Gaol, if one wishes to be historically picky) has, by the very nature of its purpose, been the scene of many dramatic moments since it was constructed in the early 1840s. People have been tried there for everything from petty crime and horse theft to murder. It has been the site of several hangings, some of them public. During the First World War, it was secretly used to hold a notorious enemy agent.

But in spite of the building’s formidable fortress-like appearance, it was never intended to serve as a penitentiary. Like other county jails in Ontario, the one in Guelph was used to lock up people who had been sentenced to short-term incarceration for minor offences, to hold accused prisoners awaiting trial and to hold felons convicted of major crimes until they could be transferred to the Central Prison in Toronto (the predecessor of the Don Jail), the Ontario Reformatory, or the dreaded Kingston Penitentiary. However, on one occasion in 1908 the routine of the Wellington County Jail was disrupted by Guelph’s own version of the Great Escape – or at least, an attempt at it.

At that time Guelphites called the jail Castle McNabb, after John McNabb, the governor (chief jailer). McNabb and his family had living quarters within the complex. A window of the residence offered a good view of part of the jail yard and one of the enclosing walls.

Among the jail’s “guests” on Saturday, March 7, were three local young men; John Cox and two others named Ripley and McIntyre. Press coverage of the time didn’t state why they were in jail; only that they didn’t have long to serve. But for three other young men the prospect of the next few years was grim indeed.

Identified in the Guelph newspapers only as McAlynn, Heatherington and Daveling, they were from Palmerston. They had been convicted of burning and burglarizing a Grand Trunk Railway car for which they’d been sentenced to three years at hard labour. The three were in the Guelph jail awaiting transport to the Central Prison, and then to the Kingston pen. They should have been moved out of Guelph some time earlier, but the transfer had been delayed. Apparently, they decided to take advantage of their extended stay in the Wellington County Jail to make a break for freedom before they could be moved to an even stronger facility. Neither McNabb nor his turnkey, Mr. Everson, saw any sign that an escape plan was in the works for several weeks before the attempted breakout. The Guelph press would later say that the scheme was worthy of a plot from a dime novel or even the Alexandre Dumas novel, The Count of Monte Cristo.

Using iron slats from their cots as tools, the youths went to work cutting a hole through a thick stone wall. When completed, this would give them access to an open space called the turnkey’s yard. They took turns keeping lookout while the others dug. They had devised a series of whistles that served as a warning system if a guard approached. As stones were pried out, they were hidden in a space under the floor. When the would-be escapees weren’t working, they piled old clothes in front of the hole to hide it.

Somehow, the prisoners managed to steal some boards from the jail’s coalhouse unobserved. They put together a makeshift ladder, using nails that authorities would later say had to have been smuggled in to them by someone on the outside.

On the day of the planned breakout, the conspirators burned some papers in a cell and then disposed of the ashes down a sewer. McNabb and Everson walked through the corridors looking for the source of the smell of smoke, but didn’t enter any of the cells. It was later speculated that the smoke might have been a lure to draw them into a cell where the escapees could overpower them and take their keys.

When that ruse didn’t work, Ripley picked the lock of a door, giving him, Cox and McIntyre access to the yard. The youths from Palmerston were in a different corridor, waiting to get out through the hole in the wall. There were still two large stones that had to be removed before they could squirm through. Those stones were proving to be a problem, and Cox thought they might have better luck tackling them from the outside.

Before going to work on those obstacles, Cox decided it would be a good idea to take a look over the jail yard wall. He put the ladder in place and climbed up while Ripley held it steady. McIntyre kept watch for McNabb and Everson. Inside the jail building, McAlynn, Heatherington and Daveling anxiously waited for their friends to remove those last two stones.

From the top of the wall, Cox could see the street on the other side. But he could also see into the window of the McNabb residence. Standing at that window and looking out, right at him, was McNabb’s son.

Cox clambered back down the ladder, but young McNabb had already shouted for his father. The chief jailer and the turnkey hurried to the yard. They found Cox and company in the coal house, busily shovelling coal and pretending to know nothing about the ladder or the hole in the stone wall.

As the local press put it, the attempted escape “landed the young desperados deeper than ever in the dark interior of the jail.” Under questioning Ripley confessed – that Cox was the ringleader. The plan wasn’t for all six of them to escape, he said; only the three Palmerston boys who were headed for Kingston.

Whether or not that was true, the failed escape plot got McAlynn, Heatherington and Daveling an extra three months added to their sentence in the Kingston pen; and Cox, McIntyre and Ripley an extended stay in Castle McNabb