December of 1945. Seventy-five years ago, the people of Guelph looked forward to celebrating their first peacetime Christmas since 1938.

Since the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, they’d endured six long years of hardship and sacrifices; from daily inconveniences to the most profound of personal losses. They’d borne it all stoically with no idea of when it would end, but nonetheless with the understanding that every individual contribution was toward a common cause; that they were all in the struggle together.

The war in Europe had ended the previous May, and the one with Japan in August. Now the peacetime Christmas that seemed like it might never arrive was coming at last.

But the privations of war hadn’t ended just because the shooting and bombing had stopped. Canada wasn’t as badly off as war-torn Europe, which was in the grip of a bleak, cold, hungry winter. British authorities had estimated that it would take five years to remove all of the unexploded bombs the blitz had left in their country.

But Guelphites and their fellow Canadians still faced a long road back to normalcy.

Many commodities such as meat, dairy products and other food item were still rationed. In fact, the Guelph newspaper reported in mid-December that butter rations would be cut in half in January. Many Guelph residents complained that local restaurants were using lingering wartime conditions as an excuse to charge prices that were “dearer” than those in other communities. Guelph coal dealers were concerned that the fuel situation in the city would soon become “very serious.”

The war industry had devoured so much of resource material that would otherwise have gone to domestic industry that store shelves, particularly those of hardware retailers, were lacking many products. New electrical appliances were scarce, and department stores couldn’t keep up with the sudden demand for men’s clothing needed by returning soldiers. Even dental supply houses, which had been stockpiling equipment and supplies for the Army Dental Corps, wouldn’t release any of it to such institutions as the Guelph Board of Health for the benefit of schoolchildren due to instructions from the Department of Pensions and Veterans Affairs.

Men and women who had been serving with the armed forces overseas were arriving back in Guelph every week. People turned out to greet them at the train station even when the weather was bad. Some, like Gunner William John Carter of the 63rd Battery and Captain G.M. Wright of the 16th Battery who had landed at Juno Beach on D Day, came home wounded. At St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Guelph-born Brigadier General Kenneth Torrance, who had survived a Japanese POW camp, unveiled a communion table dedicated to war veterans.

All the returnees were looking forward to their first Christmas at home in a long time. A few of the men brought home war brides who would be celebrating their very first Canadian Christmas. Many of those people looked beyond Christmas into uncertainty because thousands of returned veterans had no jobs waiting for them. Re-adjusting to a peacetime economy was a slow process.

Still, they knew they were the lucky ones. In too many Guelph homes, empty places at the dining room table would make that first peacetime Christmas dinner a bittersweet occasion. Financial troubles could be fixed. Lost lives were gone forever.

Downtown Guelph’s street decorations had gone up in the spring to celebrate VE Day and had been left up following VJ Day. Now they were joined by a 40-foot Christmas tree in front of city hall. Traditionally, Guelph’s downtown yuletide tree had come from the city’s Arkell Springs property, but the bushland there was now conserved to protect the local water supply.

This time the tree had been “imported” from Rockwood. Guelphites complained that it wasn’t as luxuriant as previous trees, and Guelph Parks Department employees had to pad it with extra branches. Mayor Gordon Rife tried to purchase extra strings of coloured lights for it, but they weren’t available due to a shortage of electrical wire.

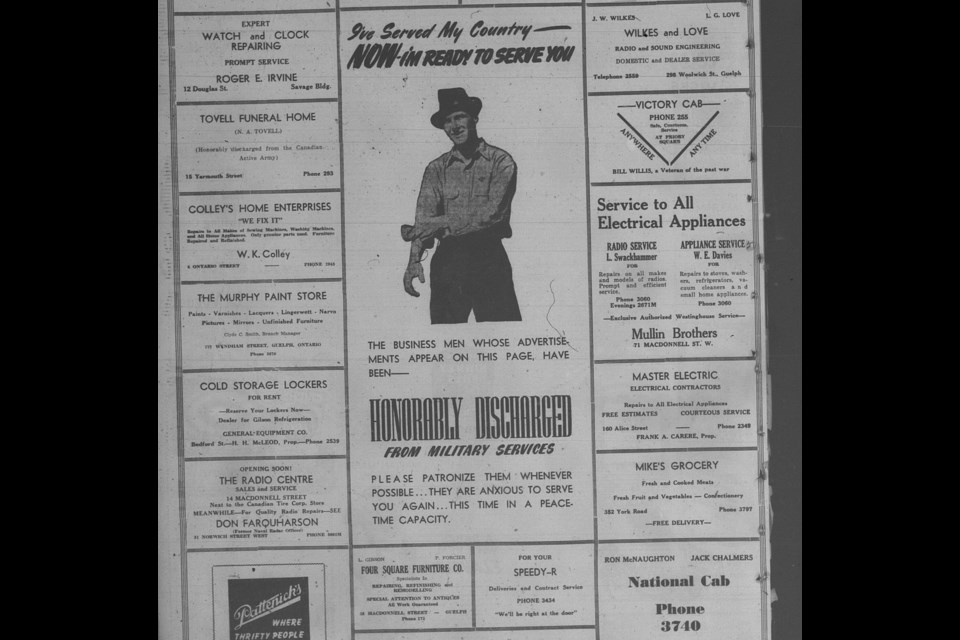

In spite of rationing and shortages, the Guelph newspaper reported that local people were setting a Christmas buying record. The city’s merchants had launched a “buy it in Guelph” campaign urging customers to shop in town instead of bigger centres like Toronto. In addition, shoppers were encouraged to patronize businesses run by returned soldiers who had been honourably discharged from military service. “I’ve Served My Country – Now I’m Ready To Serve You” said one newspaper ad.

Guelph stores advertised Christmas gifts for everyone in the family.

At Cole Brothers a woman’s full-length coat of dyed rabbit fur was on sale for $98.50. The Ros-Ann Shop had everything from sweaters and skirts at $2.98, to ski-jackets at $6.98. At Liggett’s Rexall Drug Store, a gift-pack of Seaforth shaving products for “strictly masculine grooming inspired by a famous Scottish regiment” cost just $4.99. Walker’s Toytown Circus had plenty of gifts for children. Stores now carried “New Post-War Kleenex; softer, stronger and whiter than ever before,” and endorsed in newspaper ads by cartoon character Little Lulu. Tissue paper came in handy if wrapping paper ran short.

Ryan’s Department Store provided customers with an opportunity to buy gifts and place them under a tree for special recipients; veterans in hospitals. “Let us make sure that the Christmas of these hospitalized veterans will be made as bright and as cheerful as possible,” said the store’s ad, “since they still cannot gather around their own fireside at this peacetime Christmas.”

A small show of gratitude for those whose unselfish sacrifice had helped to make a peacetime Christmas possible.