When people talk about famous criminal lawyers who have been counsel for the defence in dramatic murder trials, the names that often come up are those of celebrated courtroom giants like Clarence Darrow in the United States and Canada’s Edward Greenspan and Clayton Ruby.

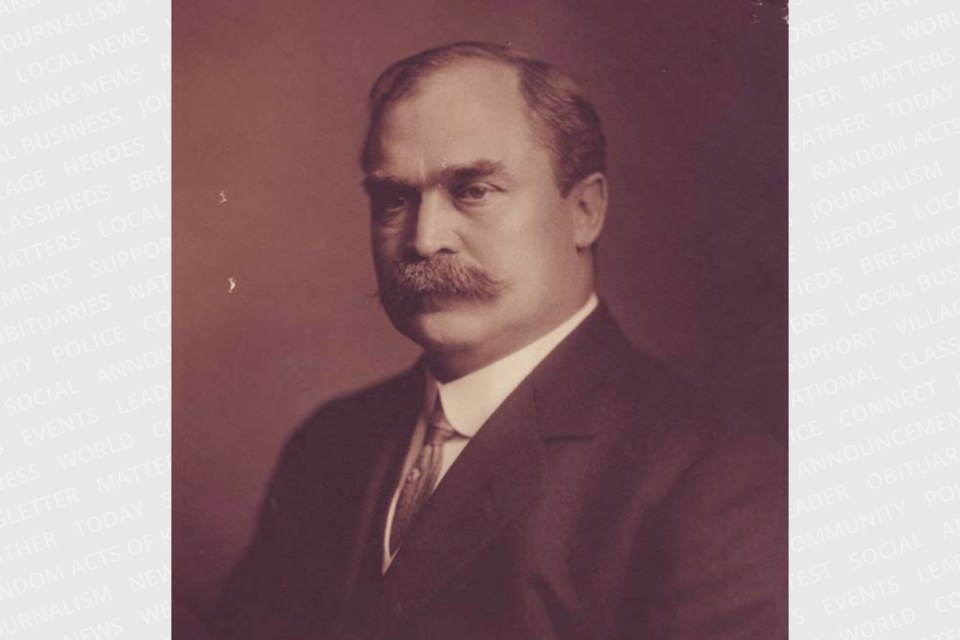

But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries there was another man who was the lawyer you wanted in your corner if you were in serious trouble with the law. E.F.B. Johnston of Guelph was considered to be one of the best criminal lawyers in Canada.

Ebenezer Forsyth Blackie Johnston was born in Haddington, Scotland, in 1850. He was just a young boy when his family immigrated to Canada West (Ontario) and settled on a farm in East Garafraxa Township. Young Ebenezer attended the Guelph Collegiate, and following graduation he taught elementary school.

In 1872 Johnston became a member of the Law Society of Upper Canada and a student-at-law in Guelph. That meant he was enrolled in an accredited degree program of law and could perform some of the services provided by lawyers.

He was sworn in as a solicitor in 1876, and called to the Ontario bar in 1880.

While practicing law in Guelph, Johnston also became involved in politics. He was a prominent local member of the Liberal Party, and drew the attention of Oliver Mowat, the premier of Ontario and the province’s attorney general.

In 1885, Mowat made Johnston deputy attorney general and clerk of the Executive Council. However, he was obliged to resign those positions in 1889 due to his growing criminal law practice, although he held the post of inspector of registry offices from 1891 to 1894.

In 1890 Johnston was appointed Queen’s Counsel (QC), which meant he was recognized as a lawyer of exceptional merit. He was known as a skilled courtroom defence lawyer who was a master at cross-examination. According to noted Toronto journalist Hector W. Charlesworth, Johnston dealt with the facts of a case “with the coolness of a mathematician.”

When faced with a prosecutor who had a greater reputation than his own, Johnston would turn that situation to his own advantage. While addressing the jury, he would win them over by presenting himself as the hapless underdog in an uneven struggle against a mighty foe.

One of Johnston’s most famous cases was that of Clara Ford. On an October evening in 1894, 18-year-old Frank Westwood was gunned down on the doorstep of his home in an exclusive Toronto neighbourhood. There were no witnesses to the murder, but an informant told police the killer was 33-year-old Clara Ford, a woman of mixed black and white parentage.

Ford worked as a seamstress and lived in a tiny apartment in a poor part of town with her teenage daughter. Her husband had abandoned them. She was known to carry a gun for protection.

She allegedly was acquainted with Westwood, and according to rumours he and his friends ridiculed her with racist taunts.

Police arrested Ford and charged her with murder. Soon, they had her “confession” in which she said she’d shot Westwood because he had sexually assaulted her. Because it was a homicide case, a guilty plea was inadmissible. There would have to be a trial.

The newspapers speculated that a first-year law student would have no trouble getting Clara Ford convicted. Nonetheless, the prosecution was handled by Britton B. Osler, a powerhouse attorney who had successfully prosecuted Louis Riel for treason.

Clara Ford couldn’t afford to hire a lawyer, so Johnston decided to take her case pro bono. He suspected police detectives under pressure to solve the murder of the son of a prominent Toronto family had bullied her into making a false confession. Moreover, the informer who had accused her was

a felon with a long criminal record whose word could not be trusted.

In a sensational trial, Johnston made tatters of the confession and the Crown’s weak circumstantial evidence. He put Ford on the witness stand – a rare move in a capital murder trial – and allowed her to tell her own story. She testified Westwood had never laid a hand on her; that the story of a revenge killing for sexual assault had been fabricated by the detectives.

Johnston won Ford an acquittal. The Westwood murder was never solved.

While Johnston was fighting for Clara Ford’s life, another murder case was developing.

Twin brothers Harry and Dallas Hyams were the black sheep sons of a genteel New Orleans family. They moved to Toronto because, it was rumoured, their more respectable relatives wanted to keep them at a distance. They operated a warehouse, and Harry married a local woman named Martha Wells. He hired Martha’s teenage brother Willie as a warehouse worker.

In 1894, insurance company investigators became suspicious when Harry tried to take out several life insurance policies on his wife. A year earlier, an insurance company had paid out $30,000 when Willie was killed in what was officially determined to be an accident at work.

The grieving Martha hadn’t been aware that the twins had convinced Willie to purchase life insurance. Now they wanted to insure Martha for $250,000.

The Toronto police decided to look into the death of Willie Wells. In February of 1895, they charged the Hyams twins with murder.

The Hyams family didn’t win any public sympathy for the twins when they sent a high-profile New York attorney to Toronto because they didn’t think any Canadian lawyers would be competent enough to defend Harry and Dallas. However, the American lawyer was not a member of the Ontario bar and so could only serve as an advisor on a legal team headed by the lawyer from Guelph.

Johnston’s brilliant cross-examination of the Crown’s medical experts showed they could not agree on how Willie had been killed. Johnston presented his own witness who said Willie had a habit of not handling equipment properly. The Hyams twins were acquitted and quickly departed for the United States.

Johnston was successful in many other noteworthy cases. He turned down several offers to run for a seat in the legislature. He died in Toronto in 1919.