Guelph recently has had the distinction of being listed as one of the most expensive communities in Canada in which to rent a place to live. A low vacancy rate and an increase in the average monthly rent being charged for apartments have combined to make the rental market in Guelph a pricey prospect for would-be tenants, especially in a university town.

But if you’re a student (or anyone else) frustrated over not being able to find an affordable place to call home in the Royal City of the 21st Century, imagine being a veteran of the Second World War, with a family, unable to find accommodations in the winter of 1946 – and then having to settle for a cabin smaller than the average living room.

With the war over in both Europe and the Far East, and thousands of service men and women returning to their communities, housing was in great demand in Guelph, and rents were high. The economy was in relatively good shape, but there just weren’t enough homes to go around. Young people who had left their parents’ homes six years earlier to join the armed forces were now full-fledged adults – some of them newly married – who wanted places of their own. Moving back in with mom and dad was not a long-term solution.

The author of an article that appeared in the Guelph Mercury that March had evidently been looking very hard for a silver lining in the situation. Under the headline The Housing Shortage Has Made Canadians Appreciate Home, the journalist explained:

“Before the war, ‘home’ was rarely good enough for the average family. If they rented an apartment they were eternally dissatisfied because people overheard, made too much noise; or the landlord was slow about redecorating; or the neighbourhood wasn’t convenient enough to work, movies, stores, etc. … Young home owners were always complaining that the house they had wasn’t large enough … older couples with a large house after their family had grown and gone found too much space a reason for complaining.

“Nobody is so hard to please now. Anybody who has or can manage to get a roof over his head feels lucky. The family is a little cramped? So what? Bedrooms that aren’t being used? You’d better not complain or your friends will all start wondering why you aren’t generous enough to rent them out to veterans … The Canadian home has never been so deeply appreciated, so lovingly forgiven all its faults since pioneer days.”

However, there were people who probably didn’t care to be lectured on how they should be grateful for what they had – the ones who didn’t have a place to call home. Notices like these appeared regularly in the want ads section of the Mercury:

“WANTED: APARTMENT OR SMALL house for businessman and wife. Have no children.”

“FUGITIVE FROM CANADIAN ARMY, wife and son let loose on relatives, desires house, flat, apartment or anything immediately or sooner.”

“EX-AIRMAN, wife and small child, want apartment or three rooms suitable for setting up housekeeping. Best of references will be furnished.”

Among those caught in the housing crisis was J.A. Galarneau, formerly of Quebec City. During the war, Galarneau had served in the RCAF and the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC). For much of the time he’d been stationed in Newfoundland. When the war ended he was discharged and then managed to line up a factory job in Guelph.

He arrived in the city in February of 1946 with his wife and four children aged eight, 10, 14 and 16.

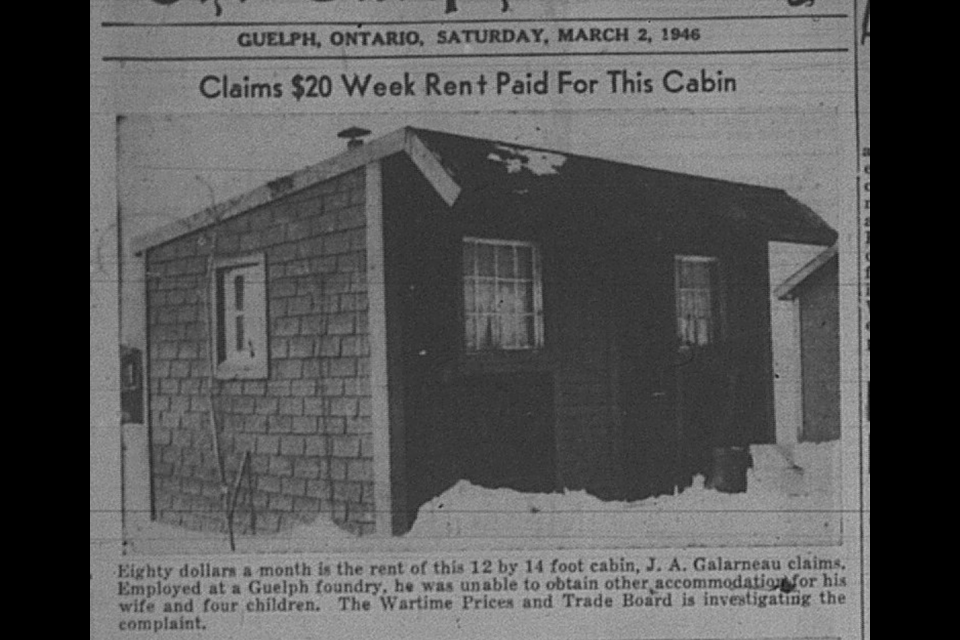

To the parents’ dismay, they could not find a place to rent anywhere in the city. They wound up in a 12 x 14 foot cabin at a camp ground called the Blue Bird Cabins on what was then known as the Kitchener Highway (# 7). Rent for the tiny, one-room dwelling was $20 a week – the equivalent of about $300 in 2023 funds.

The cabin was too small for the whole family, so Galarneau boarded the two older children with a local farm family for $10 a week. His pay from the factory job was $32 a week, leaving him with $2 to feed himself, his wife and the two younger children. Now, Galarneau claimed, the landlord wanted to evict them because they were burning too much coal to keep the cabin heated.

The family’s plight made headline news in the Mercury. It drew the attention of the Wartime Prices and Trade Board officer, as well as the Guelph branch of the Royal Canadian Legion. While the WPTB investigated the situation, the legion helped the Galarneaus out financially.

“We are very incensed that a veteran should have to pay that amount of rent,” said Legion pensions secretary Jack Nevin. “There is no doubt the man is a bona fide veteran. He is being helped by the Legion Welfare fund until the matter is settled.”

The landlord told the Mercury that the situation had not been accurately reported. He said he was not in the habit of turning families out into the cold, but that he had agreed to allow the Galarneaus to take the cabin for only a few days because they had nowhere else to go. He said he was willing to refund any money Galarneau had paid him if the family would just vacate the premises.

The Mercury did not report on how that particular situation was finally resolved.

However, the Mercury did keep its readers informed on what was happening at city hall. Some councillors said the housing crisis would “right itself” in time. Others pressed for immediate action.

Plans were made to allow the construction of small, frame “wartime houses” on lots provided by the city. Rents would be $35 to $45 a month, and priority would be given to veterans.

City hall was soon inundated with requests for information about the “snug” little houses, even though some people warned that they would be little more than shacks, not much better than the one the Galarneau family had been in. There was also concern that the city would be able to build 100 such houses at most and that still wouldn’t solve the housing crisis.

Guelph’s population today is many times what it was in 1946. The housing problem, evidently, has been keeping pace.