Most Guelphites with any knowledge at all of Canadian art will be familiar with such names as those of the Group of Seven and their colleague Tom Thomson, as well as Emily Carr, Ken Danby and Kitchener’s Homer Watson. However, there was another artist whose name they probably don’t know – no street named after him and no representation of artistic works on postage stamps – and yet, he was once a resident of the Royal City and captured various Guelph locales in his work. His name was David Johnson Kennedy.

Born in Port Mullin, Scotland, in 1817, David was the son of William Kennedy, a stone mason, and his wife Elizabeth. He was educated at a local school, but at an early age was put to work by his father as a labourer and apprentice at construction sites. The boy hauled gravel for a road leading to a lighthouse his father was building. When young David said he wanted to be an artist, William laughed.

Nonetheless, the elder Kennedy taught his son architectural drawing and allowed him to further his education at the Leswalt Academy. Young Kennedy was otherwise self-taught as an artist.

The Kennedy family then moved to Ireland, where David’s father worked on harbour construction. David was employed hewing stone blocks. He was also allowed to take a few lessons with Belfast artist Robert McMeiken.

In 1833 the Kennedys immigrated to Canada, where they’d heard there was plenty of work for stonemasons. On the voyage to Quebec City, David made a watercolour of ships off the coast of Newfoundland. When they moved on to Kingston, where there was employment for both father and son, David made a sketch of the city’s harbour.

The two Kennedys worked on the Bank of Kingston and then on the Kingston Penitentiary. However, after the elder Kennedy apparently lost their money to a swindler, the family turned to farming. They settled on a homestead on the Elora Road, six miles from Guelph. They called the farm Spence Bank after David’s mother, whose maiden name was Spence.

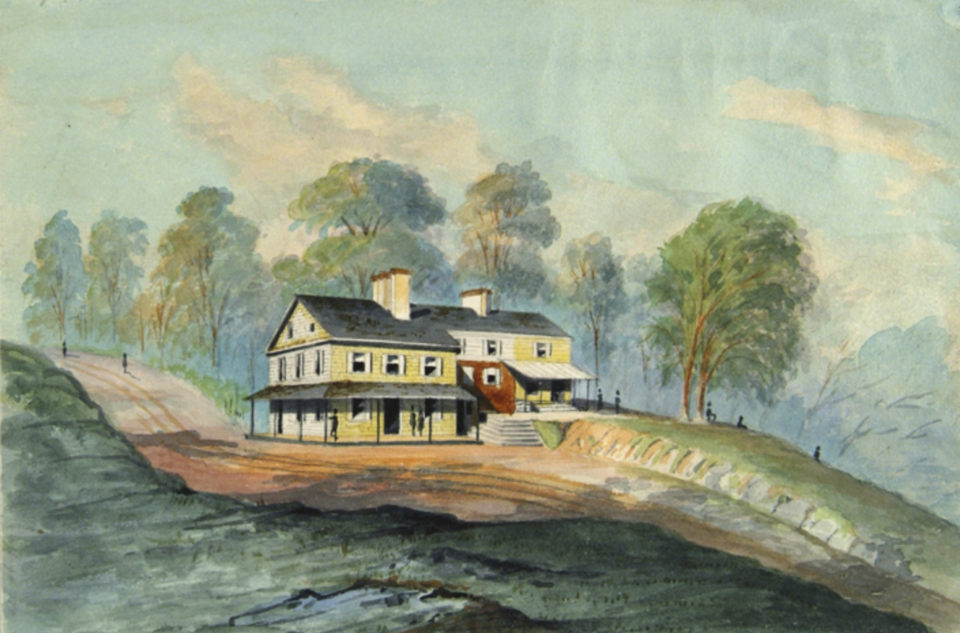

David worked for a while as a stonemason in Hamilton, but by this time he had come to hate the trade. He rejoined his family to help his father on the farm. They built a log house in what was called the stockade style. It earned William the nickname “Upright Kennedy” because the vertical style was unlike anything used by other settlers. An 1835 watercolour of the Kennedy property was one of David’s earliest paintings of the Guelph area.

Farm life was hard. Young Kennedy found the work exhausting. The fact that Guelph was still a frontier community was made very evident one day in the winter of 1834-35 when, while returning home from a barn-raising, Kennedy had a close call with a pack of wolves.

In 1836 Kennedy went to visit a sister in Philadelphia. On his way through Hamilton he sketched Miller’s Hotel. From Philadelphia he moved on to Nashville where he was employed at a store for ladies. He wrote that he “made the acquaintance of all the rich planters’ daughters who knew how to spend money.” He found a new source of income – painting miniatures.

Kennedy returned to Guelph in 1837 and painted another watercolour titled Spence Bank. It might have been an image of the family’s original log house converted to an expanded regency-style cottage which showed how the Kennedys had prospered. But David once again found farm life not to his liking, and he moved back to Philadelphia.

In 1839, Kennedy married Morgiana Corbin of Philadelphia. He also took a position with the Reading Railroad as a passenger and freight agent, a job at which he would be employed for 23 years. That same year his parents sold Spence Bank and joined their son in Philadelphia where David helped his father find employment with the railroad. Eight years later, William, now a widower, returned to Guelph to live with a married daughter. He built a house on a parcel of land he purchased from future prime minister John A. Macdonald and called it Yankee Cottage.

Although David was an employee of the railroad, he devoted much of his time to his art. He drew and painted numerous street scenes and other views of Philadelphia. One of the best known is a nautical scene called Entrance to Harbor – Moonlight, a highly finished drawing in black and white with almost invisible small touches of orange and green pastel. He used a method of scratching the grey colouring of the pencil to reveal the white paper below to produce the glow of the moon, the luminosity of clouds, the foamy surf, and the glint of light on sails.

Kennedy exhibited at the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Academy, and the Artist’s Fund Society. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania would one day own more than 650 of his watercolours.

David Kennedy never returned to Guelph to live, but he might have intended to do so. In 1850 he bought a lot next to Yankee Cottage and arranged to have his father build him a two-storey house of Guelph stone. However, after the cellar was dug and the foundation of the house was laid, David sold the property to his brother-in-law, Charles Davidson, who built a rubble-stone house he called Sunnyside.

Kennedy frequently visited Guelph and produced watercolours of local landmarks, including Yankee Cottage. He made notes on the backs of some of them, such as “… sketched from the brow of Strange’s Hill … showing where the first tree was cut in locating the city, the stump of which is shown in front of the horse and sled leaving the mill.”

After he retired from the Reading Railroad, Kennedy worked briefly as a draughtsman for the city of Philadelphia. Even in full retirement, he was not idle. He continued to produce works of art and invented a device called the Philadelphia busybody” which used an arrangement of mirrors to allow an occupant of a house to look up and down a street at the same time.

Kennedy died in Philadelphia in 1898. Only one example of his work, an ink drawing, is in the Public Archives of Canada, but in 1973 the University of Guelph acquired six of his Guelph watercolours – an important part of the artistic record of early Guelph.