Over the past century, Guelph has been hometown to several boxers who made their mark in the ring. In an era when a night out at “the fights” or an evening in front of the radio or the TV taking in the action in the ring was a popular form of entertainment, Guelph fighters were often on the card both locally and in larger centres like Toronto, Montreal and Buffalo.

In the 1920s and ‘30s we had Ontario amateur light-heavyweight champion Cosmo “Cutts” Carere, Canadian Boxing Hall of Famer Peter “Punching Pete” Zaduk, and Canadian welterweight champion Jackie Keegan, who was also the Canadian Armed Forces welterweight champion for Central and Western Command from 1942-44. In the 1940s Guelph boxing fans cheered for a trio of battling brothers; Marshall, Ernie and Harvey Keleher, whom the sports writers dubbed the Klouting Kelehers.

In the 1950s, Pat Campbell, a lightweight and welterweight whom the Toronto newspapers called “the rugged young slugger from Guelph,” was a fan favourite. Campbell’s hometown supporters would often make the trip to the Palace Pier in Toronto to cheer him on. If a decision went against Pat, the Guelph contingent would loudly make their displeasure known.

Even though Guelph boasted its own pugilist heroes, perhaps the city’s biggest boxing-related thrill came the day the heavyweight champion of the world came to town. Tommy Burns (real name Noah Brusso) was, to date, the only Canadian-born world heavyweight champion. He was born in Normanby Township near Hanover, Ontario. His family eventually moved to Galt – close enough for Guelphites to consider Burns a neighbour once he became a celebrity.

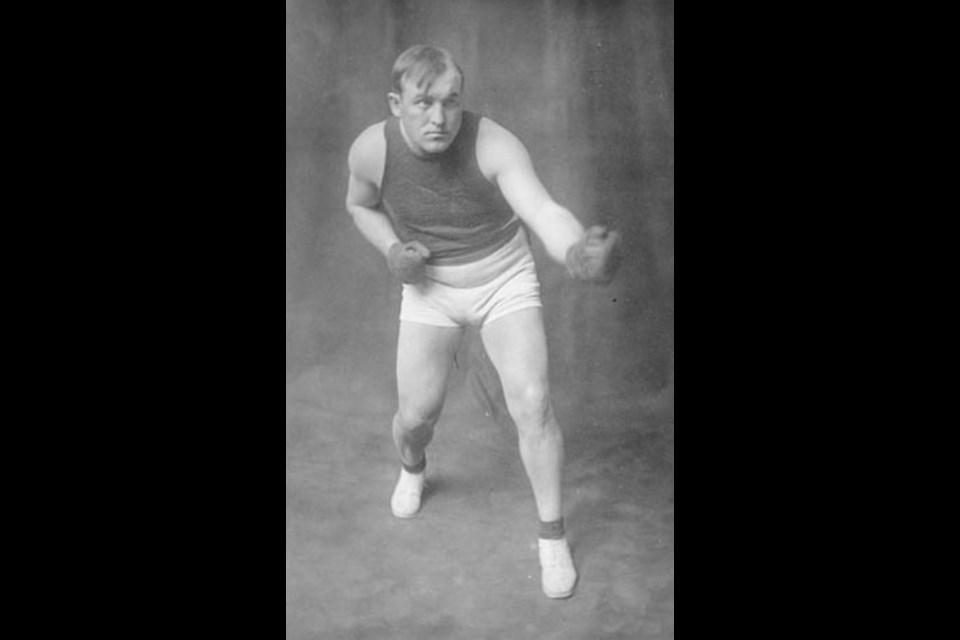

At five-foot-seven and weighing about 175-180 lbs., Burns barely qualified as a heavyweight. He usually found himself punching above his weight against bigger men who had a longer reach. He was the underdog when on Feb. 23, 1906, he took on the champion, Marvin Hart, in Los Angeles. Burns won the 20-round bout by decision.

On Feb. 4, 1907, Burns arrived in Guelph by train with his sparring partner, Jimmy Burns of Toronto, and several other boxers. He had already defended his title and had let it be known that he would take on any challenger, anytime, anywhere; but he and his colleagues were in Guelph only for exhibition matches at the Royal Opera House. It was part of a 10-week tour for which the champ was being paid the astronomical sum of $1,000 a week.

In an interview in his room at the King Edward Hotel, Burns told the local press he was always willing to take chances. “Didn’t I take a chance at Marvin Hart, and all of you fellows up here thought I would be a chopping-block for him. Well, didn’t I trim his sails to the King’s taste! Sure, I did.”

Burns reminded his listeners of other fights he’d won over formidable opponents, but he tempered his self-praising with a dose of boxing reality.

“I’ve given medicine out to others, and some day I must be taking medicine myself. It’s all in the game.”

When a reporter pointed out to Burns they were only 14 miles from his home in Galt, he responded, “Gee! I can’t let that chance pass of seeing mother. We’ll drive down tomorrow, sure, and be back in time for the show at the Royal Opera House.”

The highlight of that show was a six-round match between Tommy Burns and Jimmy Burns. The local paper reported that while the audience could not expect the fighters to “cut loose,” they nonetheless were treated to a display of “quick ducking, side-stepping, and the panther-like agility of the big fellow, who is an exponent of the modern school of boxing.”

Guelph journalist Hereward K. Cockin remarked in his column that “members of the unco guid (rigidly righteous) in town” no doubt objected to the boxing demonstration at the Royal Opera House. He noted there were no parsons among the doctors, lawyers, merchants and other respectable citizens in the audience. Pugilism, like horse racing, was frowned upon in puritanical circles.

“It is rather a pity,” Cockin wrote, because they would have seen “how utterly lacking it all was in the slightest objectionable feature. Rather, it was a series of manly exhibitions of skill, quickness and endurance.

“There isn’t a man amongst us with good red blood coursing through his veins who didn’t feel some thrill of satisfaction when a not distant neighbor of ours was found fit and able to hold his own amongst the first-raters in the heavyweights. And we don’t feel any the worse because this man has proven to be a decent fellow.”

It appeared that most of Guelph’s “red-blooded” citizens agreed with Cockin. The Royal City was pleased to have had the champ as a guest. But as Burns had predicted, the day came when he had to take the “medicine.”

On Dec. 26, 1908, in Sydney, Australia, Burns lost the title to Jack Johnson, making Johnson the first African American heavyweight champion. Speaking to a crowd of people in Vancouver in 1909, Johnson said, “Let me say of Mr. Burns, a Canadian and one of yourselves, that he has done what no one else ever did, he gave a black man a chance for the championship. He was beaten, but he was game.”