There was a time when the Speed River was popular with swimmers. Riverside Park was a favourite place for local residents to go for a picnic and a dip. There were other locations along the river that were known as good swimmin’ holes.

One was the site of the Heffernan Street pedestrian bridge (not the present structure). It was, in fact, a place much favoured by skinny-dipping boys.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a belief among some boys that only “sissies” wore bathing suits when the gang went swimming. This notion was not restricted to Guelph.

Articles from Toronto newspapers of the period tell of complaints about naked boys swimming in the gaps between the mainland and the Toronto Islands. Investigating reporters and police learned that boys from poor families who couldn’t afford bathing suits would ridicule boys from more affluent backgrounds who had the affrontery to wear “swimming costumes.”

Dispensing with swimming attire removed class distinctions.

Whether or not that was the case in Guelph, too, it wasn’t always an acceptable excuse for nudity as far as people who lived near the Heffernan Street bridge were concerned. There were complaints, especially from one woman who didn’t particularly care for the sight of naked boys jumping into the river.

Some of the lads did their skinny dipping at places a little more removed from the public eye, though it’s not certain if that was because of complaints or because the swimmers themselves preferred a more private locale.

All too often, the Mercury reported on drownings. Over the years, the Speed River claimed many victims. People tend to underrate the danger of fast-flowing water, and kids frequently swam without any adult supervision.

Parents didn’t always know that their children were swimming, which could be the case when a group of boys decided on the spur of the moment to take off their clothes and jump in – having given no indication when they left home that they would be going in the water.

Nor was it always necessary for people to actually be swimming in the river for a terrible accident to happen. Someone who was too close to the water might simply fall in and be unable to get back on the land. Before flood control measures were put in place, high-water conditions after heavy rain or spring melt made the Speed even more dangerous.

One drowning tragedy happened on May 31, 1907. Cousins Robert and Albert Brown, both age five, and Robert’s brother, three-year-old Frank, were playing in the vicinity of Johnston’s boathouse under the supervision of Robert and Frank’s mother. She didn’t notice the three little boys had wandered away until Robert and Albert came running to tell her that Frank had fallen in the river.

Mrs. Brown frantically told Charles Spires, a boathouse employee. Spires searched the riverbank in the area where the boys said Frank had fallen in. He found the

child’s hat in the water. He then launched a boat and discovered the small body floating nearby.

A few weeks later, tragedy struck again. Andrew Stewart, believed to be about 19, was from Ayrshire, Scotland. He’d been in Canada less than a month, and had been sent to Guelph by the Commercial Bank of Scotland to work in the local branch of the Dominion Bank.

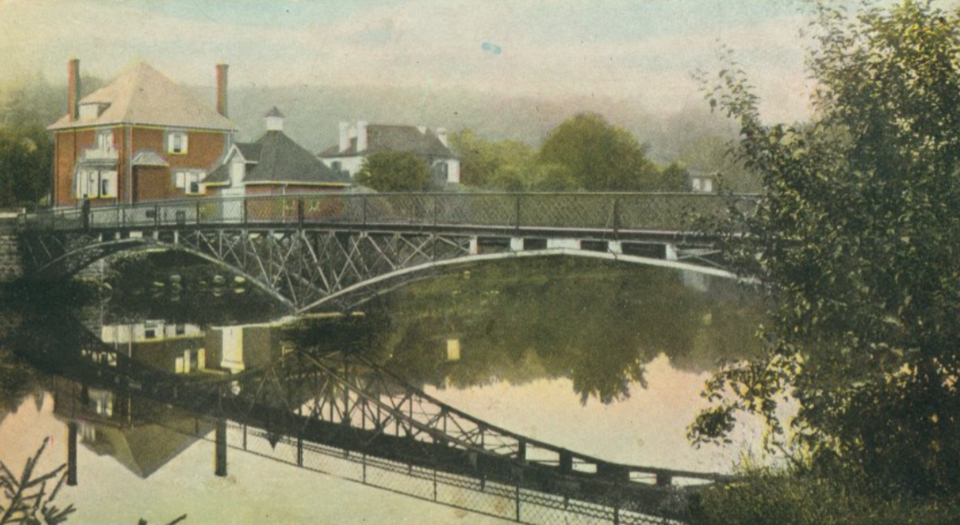

On Saturday, June 22, Stewart went for a hike with four other youths: Vernon Steele, Ernest Jones, F. Paton and Reginald Parker. They walked along the Eramosa River, which at that time was considered an extension of the Speed and was sometimes called the “city branch.” They reached a location that was then called Victoria Park where there was a bridge of the same name. It was a rural area, and the river was 10 feet (three meters) deep in the middle, so it was a good place for skinny dipping.

There was a steep drop to deep water on one bank, but on the other side there was a gentle slope and several large stones that jutted into the river.

According to the Mercury, “On reaching the river bank all of the party stripped off their clothing and plunged into the water, with the exception of young Stewart, who had previously remarked that he could not swim.”

For a little while the four youths splashed around while Stewart watched from the bank. Then Jones and Paton, who were both strong swimmers, swam upstream to a bend in the river about a quarter of a mile away.

Steele and Parker, who were only fair swimmers, stayed near the bridge. They had grown tired and were heading for the riverbank when they saw that Stewart had taken off his clothes and was walking along the stones into the water.

What happened next, the Mercury said, “will perhaps never be distinctly known, as both of the deceased’s companions were themselves nearly drowned and feel very badly over the matter.”

It seems that Stewart ventured out into water that was over his head. He panicked and swallowed water. Steele tried to catch hold of him, and got an arm under Stewart’s armpit, but Stewart “grappled with him and both were pulled under water.”

Parker saw the two were in trouble and swam out to help. He managed to get hold of Stewart, allowing Steele to free himself, though he did so with difficulty. Steele was barely able to make it to shore.

Now Parker found himself in a struggle with Stewart. In his panic, Stewart wrapped his arms around Parker’s neck and dragged him under. Parker managed to break free and get to the surface, but Stewart sank out of sight.

Parker made it back to shore, and then he and Steele ran upstream to get their friends. Jones and Paton dove to the bottom several times to search the murky water, but couldn’t find Stewart.

Meanwhile, the other two went for help.

Soon chief of police Frederick Randall was on the scene with a constable and another man. Using two boats and a grappling line, they succeeded in retrieving Stewart’s body.

H.C. Scholfield, manager of the Dominion Bank, had the sad task of informing Stewart’s family in Scotland.

Stewart had no relatives in Guelph, but a large number of residents, including Mayor John Newstead and many of the city’s leading citizens, turned out for the unfortunate young Scot’s funeral at Knox Church.