The recent passing of Rosalynn Carter, wife of former American President Jimmy Carter, serves as a reminder to us that people in positions of power usually have someone – a spouse or other significant partner – on whom they depend for support, inspiration and guidance.

Prior to the highly-publicized marriage of Pierre Elliot Trudeau to Margaret Sinclair, the wives of Canadian prime ministers usually stayed out of the limelight. Nonetheless, some of them were known to be remarkable sources of strength for their husbands.

One such was Olive Diefenbaker, wife of Canada’s 13th prime minister (from 1957 to 1963). She was also once a resident of Guelph.

John Diefenbaker was the Progressive Conservative prime minister who is probably best remembered for controversially scrapping Canada’s technologically advanced fighter aircraft, the CF 105 Avro Arrow, and for his opposition to Canada’s official adoption of the maple leaf flag over the old red ensign, which had been the nation’s de facto flag since the 1870s. Olive Diefenbaker rarely spoke publicly about decisions and policies of the Diefenbaker administration, but behind the scenes she was supportive of all that he did.

She was born Olive Evangeline Freeman in Roland, Manitoba, in 1902; one of five children of Dr. Reverend David Freeman and Angie Alicia (nee Eaton). The Freeman family had strong roots in Nova Scotia. Both of Olive’s parents were of United Empire Loyalist stock. She could trace her ancestry back to Massachusetts and the pilgrims who had landed at Plymouth Rock on the Mayflower.

As a clergyman, David Freeman was assigned to baptist churches at several communities in Ontario and the west. The family was living in Saskatoon in 1917, when Olive first met John Diefenbaker at a church event. She was only 15 years old and he was 22, so there was no instant romance. Their eventual marriage would not even be a first for either of them.

Olive attended the University of Saskatchewan and Brandon College, and then went to Toronto where she earned a high school teaching diploma at the Ontario College of Education. She taught at a school in Huntsville, and then in 1929 she accepted a position teaching English, French and art at Guelph Collegiate Vocational Institute (GCVI). According to the Guelph city directory of the time, Olive resided on Oxford Street.

In a biographical sketch of Olive published in John Diefenbaker’s memoirs, she is described as a teacher who was sensitive and a good communicator and listener who imposed a discipline of the mind.

In spite of wearing a back brace because of several slipped discs, she coached girls’ field sports and basketball. She sought to gain students’ confidence and inspire them to achieve. On one occasion, Olive promoted a boy who was studying at a third-year level to the fifth-year level because his work was exceptional. The student said he was uncomfortable with that decision because he didn’t like to push himself. Olive assured him this was an important reason for her decision; that he had excelled without feeling a need to push himself. What might he accomplish, she asked, if he did push himself? The boy went on to perform beyond his own expectations.

While Olive was teaching in Guelph she met Harry F. Palmer, a lawyer. They were married on Sept. 19, 1933, and resided on Liverpool Street. A daughter, Carolyn, was born in 1934.

Olive gave up her job at GCVI. Then Harry fell ill. He died on April 16, 1937, at the age of 34. Now a widow with a child, Olive had to return to teaching. She taught at high schools in Arthur and Owen Sound. Her skills at guiding students did not go unnoticed. Olive was offered the position of headmistress at two prestigious girls’ schools. She turned those offers down, but could not refuse the opportunity to be assistant director of vocational guidance for the Province of Ontario.

Olive held that position until 1953. She was a pioneer in the developing field of student guidance and gave lectures to educational groups across Canada as well as in the United States. However, when the Minister of Education offered Olive the full directorship, she turned it down. She was about to marry John Diefenbaker, who was at that time the MP for Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

Diefenbaker was now a widower. His wife Edna (nee Brower), whom he’d married in 1929, died of leukemia in 1951. Olive and Diefenbaker were reacquainted that year, and two years later they were married.

Prior to her marriage to Diefenbaker, Olive had been outspoken on such topics as education and women’s suffrage, and she was a staunch supporter of the monarchy. After she became Mrs. Diefenbaker, she channelled her energies into helping her husband with his career. She was always discreet when talking publicly about politics.

When Diefenbaker became prime minister, Olive began the practice of holding teas for MPs’ wives. In the prime minister’s official Ottawa residence at 24 Sussex Dr., she entertained such leaders as British Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Harold Macmillan and Anthony Eden; American President Dwight Eisenhower, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and French President Charles de Gaulle.

She assisted with the writing of Diefenbaker’s speeches and often travelled with him when he was on the campaign trail. The Diefenbakers visited Guelph, and Olive delighted in showing her husband around her old school.

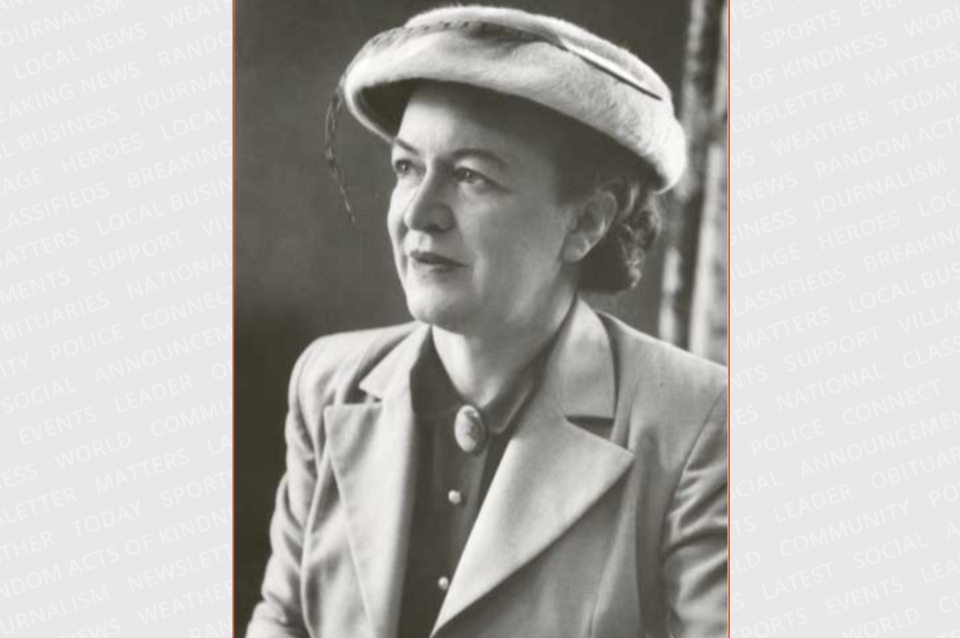

Olive always knew how to dress for an occasion, whether she was meeting the premier of a Canadian province or the queen. The dresses and hats she wore for formal events were carefully chosen to reflect her charisma, strong character and sense of class. When Diefenbaker finally went down to electoral defeat, she was the model of grace and dignity.

In 1975 Olive suffered a stroke. The following year she was hospitalized with heart disease. She died on Dec. 22, 1976, at the age of 74.

Olive had maintained lifelong friendships with colleagues and students she had known at GCVI, and with Wellington MP Alf Hales and his family. On learning of her passing, Hales told the Mercury that Olive was “a uniquely warm personality, a most gracious hostess, held in high esteem by all members of the House and a great support for her husband.”