“There’s no Hall of Fame for that working class hero, no statue carved out of stone…” – Alan Jackson

This line from Country Star Alan Jackson’s song, “Working Class Hero” so fittingly describes the community who lived and worked in a vibrant Italian neighbourhood which over time became known as St. Patrick’s Ward.

The Ward was full of working-class heroes.

Finding work was a top priority for these men and women who arrived in the Ward from Italy and other European countries with few possessions and little money.

Despite all the challenges and sacrifices they had to make, they settled in the Ward and found whatever work they could to build a new life for themselves and most importantly for their family.

With Italian immigration at its height in two waves during the 20th century, its influence became an integral part of Guelph’s character. Many moved into the Ward to be close to family and friends, and especially near factories where they found work as labourers.

Most were no more than a 10 to 15-minute walk from where they worked. When my dad, Domenico, came from Italy, he and three of his brothers, Giuseppe, Luciano, and Antonio all lived on Elizabeth Street at one time or another. For most immigrants, community meant being near family first.

I grew up in this proud working-class community of mainly Italian, Polish, Ukrainian, and Irish immigrants in the 1950s and 60s. My dad worked as a barber on Morris and Elizabeth Streets his whole life. My mom stayed at home (as did most moms in the Ward) looking after and helping to raise the family.

In the 1930s, '40s, '50s, and into the '60s people worked with their hands in many factories and plants in and around the Ward. Most did not own a car and walked everywhere to work.

The weather was never an issue when it came to going to work. There were never any “snow days.” If you didn’t go to work, you didn’t get paid.

Nothing miraculous about how we grew up. We never thought of ourselves as being poor. We never inherited truck loads of money, but we inherited something far better: We were taught that there were no barriers to what you wanted to accomplish in life if you were kind, honest, and hardworking.

The family came first: La Famiglia e tutto. It was everything. We were proud of who we were and where we came from.

NORTHERN RUBBER

My mom, Marguerite Antonette, was just a teenager when she started working at the Northern Rubber plant on the southeast corner of Alice and Huron Streets. She used a small wooden step stool so she could reach the machines.

The five-storey factory of reinforced concrete opened in April of 1920 and produced rubber-based footwear like running shoes, toe rubbers, galoshes, and later women’s velour slippers. By 1932, the workforce grew to over 750, and the plant was producing over 7,000 pairs of rubber footwear. Their market included all of Canada and many places abroad.

Orlando ‘Lanny’ Sorbara was just 15 when he started working at Northern Rubber to help support the family. His daughter Vikki remembers him telling her that the smell of the glue was so overpowering that on every break/lunch, he would go outside and throw up.

Palmira Vincentine was 18 years old when she worked at the plant in the late 1930s. She worked in what was called the quarter room, attaching buckles on galoshes. Like Lanny, she said the “stinky” smell of the rubber and the glue was just dreadful. Palmira was making $3 a day.

She recalled seeing Guelph Police on the upper floors of the plant on several occasions discreetly looking out the windows watching for organized crime activity on Alice Street.

As a young boy, Pacifico ‘Puss’ Valeriote who grew up across the street from Northern Rubber used to say that you always knew it was Sunday because it was so quiet. In the early days, all the factories and plants in the Ward were closed on Sunday.

After World War II, Northern Rubber became Dominion Rubber and then Uniroyal. The original landmark building is a prominent example of early 20th century industrial Guelph and is currently being redeveloped into an condominium complex.

BILTMORE HATS

Named after the luxurious Biltmore Hotel in New York City, moved into the Ward at the northwest corner of Morris Street and York Road in 1957. At one time, the plant shipped more than 2,400 hats a day which was more than one third of the total Canadian volume. Biltmore became a large employer for skilled Italian immigrant labour settling in Guelph.

Dominic Longo and three of his sons Frank, Mike, and Joe all worked at Biltmore. Joe worked as a Clipper in the 1950s making $27 a week. He used electric clippers to trim fur off women’s hats. Jim Sorbara spent several years at Biltmore working on the line that would check the hats for any imperfections in the felt.

Michael Raso, his brother Dominic, and Mike’s son, renowned Guelph musician Adrian Raso, all worked at Biltmore Hats.

In 2006, Adrian paid tribute to the iconic hat company in an instrumental track called, The Biltmore Blues. During concerts and his many stage performances, Adrian proudly wears one of his many Biltmore hats (matching his suits and ties), given to him by the company. Adrian is currently in the process of writing the soundtrack for a film about the History of Biltmore Hats in Guelph.

I am also a very proud owner of an original Biltmore Fedora given to me by World War II veteran Frank Taylor. Frank bought the hat in 1992 for $84.53.

Many Italian women worked at Biltmore doing the sewing work required for the hats. In the late 1950s women were paid $3 an hour and would sew upwards of several dozen hats per day. Most of the hats were made from rabbit fur, but the higher end hats used beaver fur to create the felt.

Biltmore’s association with Guelph’s Junior A hockey team, The Guelph Biltmore Mad Hatters, helped to popularize the “hat trick.” All players scoring three goals in a single game were awarded a new Biltmore hat. The company created straw, fur, the western style felt hats, caps, and later the popular ‘Rain Away Hats.’ At its peak, the plant employed over 450 workers.

Another unique aspect of the Biltmore legacy is its connection to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. At one time, Biltmore Hats in the Ward was the exclusive maker of the stetson worn by the RCMP.

The Mountie hat was made from rabbit pelt, gold foil, and patent leather.

One day I would love to own one of these Stetsons! Former Guelph police sergeant Marino Gazzola remembers buying the exclusively crafted Biltmore made Stetson in 1976 and shipping it to his cousin in Italy who collects hats from around the world.

After almost 90 years of operation in Guelph, the plant closed in 2012. The company was purchased by Dorman Pacific and production was moved to one of its subsidiaries, the Milano Hat Company in Garland Texas.

Today, the original Biltmore property in Guelph is home to 20 townhomes and a three-storey, 42-unit apartment complex.

IMICO

Leapin’ Lou Fontinato, Guelph’s famous hockey legend, grew up in the Ward and often told the story about his dad who worked at the International Malleable Iron Company for over 40 years.

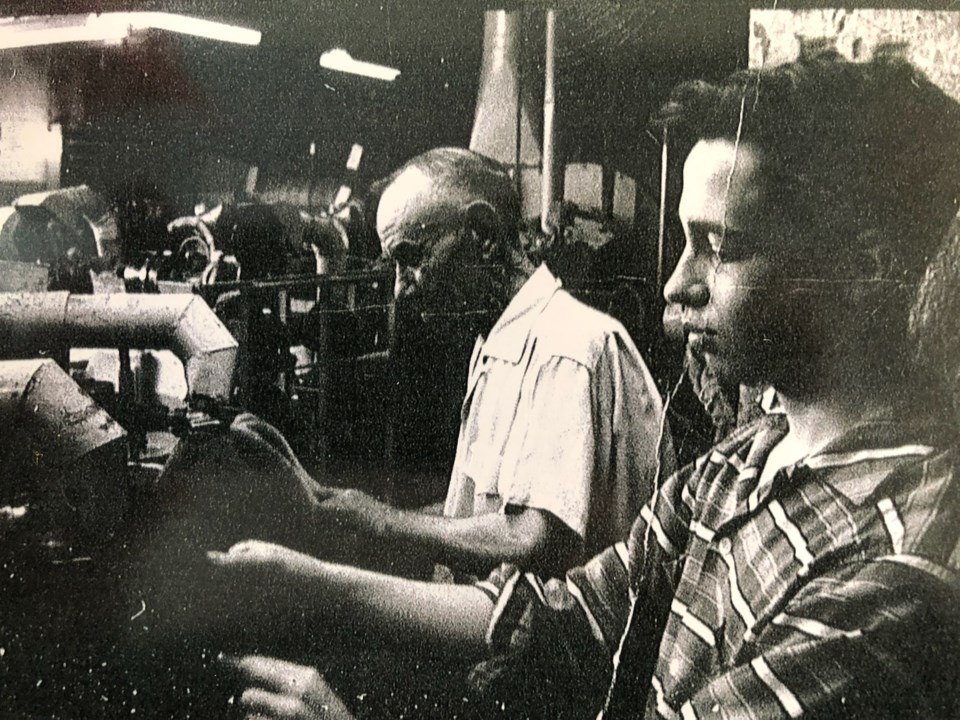

The 13-acre foundry was located northeast of the intersection between Stevenson Street South and Beverly Street. It was a major Guelph employer in the first half of the 20th century with a payroll of over 450 people. Lots of Italian, Polish, and Ukrainian workers – men, women, and young teens – all worked at the foundry.

IMICO produced grey iron pipe fittings and other metal components.

Silver ‘arnies’ of all sizes that many working dads’ brought home from the plant were a prized possession for many kids in the Ward.

John Valeriote recalls that the waste sand from the wooden casting moulds at Malleable Iron were used extensively by numerous gardeners in the Ward to loosen up the soil in their gardens. Gardens in the Ward were bountiful and the pride of each homeowner.

Like many Italian immigrants, Guido Cecchetto’s first job was at IMICO. He worked at the foundry for nearly 25 years. Nino Pol and Elio Santi also worked there pouring hot liquid iron into moulds.

Elio remembers several accidents and many close calls in the foundry when drips from the hot iron accidently spilled onto the boots of labourers on the job.

Ernesto Gazzola worked days, afternoons, and often night shifts at the plant for nearly 20 years. His son Marino remembers many times when his dad would come home from work covered in filth and almost black with dirt.

Foundry work was often hazardous, but steady employment for immigrant labourers, no matter how difficult, was a way to put food on the table and provide a home for their families.

After nearly 80 years of operating in the Ward, the iron foundry closed its doors in 1990. Today, a issue over the existence of contaminants on the former Beverly Street property is still an issue. The City of Guelph took possession of the IMICO site in 1997 and has undertaken several cleanup efforts. An agreement to sell the land for redevelopment fell through in late 2020.

MATTHEW-WELLS PICKLE COMPANY

“As good as a Rose is beautiful,” was the motto of the Matthew-Wells Pickle Company located on the east side of Victoria Road South, just south of York Road.

For nearly 40 years, the plant produced Rose Brand pickles, olives, vinegars, jams, jellies, marmalades, and sauces. The company opened in 1931 with 12 employees and by 1962 employed over 160 people.

Several of my relatives from Italy found their first job working in the plant. My zia Vincenza Tersigni worked there for several years.

It was not easy work. There were stories of workers spending eight hours a day picking the green leafy tops off strawberries with their bare hands without a break. Guido Sartor, his mom, and dad all worked at the pickle plant. Guido was 15 years old when he worked summer jobs at the plant in the 1950s. He was a relish maker and helped to unload trucks of pickles on the night shift. The pickle plant closed in 1968.

GILSON MANUFACTURING COMPANY

In 1907, a Canadian branch of the Gilson Manufacturing Company opened in the Ward at 240 York Road. For nearly 70 years the plant made everything from gas engines, farm tractors, farm tools, and furnaces to washers and freezers.

Gino Lago worked a few summers in the machine shop at Gilson’s in the mid 1940s. He was barely 15 years old and was making 10-15 cents at hour.

Lanny Sorbara’s home on Huron Street was right across from the truck entrance to Gilson’s. Noisy transports went in and out all day and as a kid Vikki says her dad would not allow her and her sisters to go out past the gate at the end of their driveway because it was too dangerous.

Huron Street was very narrow and when trucks made the turn into the plant, boxes would often fall onto the sidewalk near their home.

Gilson’s also produced specialized gas engines for farming equipment. One of their engines called Goes like Sixty, became renowned over time. The company also had a plant on Victoria Road South at Elizabeth Street. At its peak, Gilson’s employed about 300 employees. The company was shut down in 1977.

GUELPH STOVE COMPANY

Avid antique collectors are fascinated when discovering vintage pieces from the Guelph Stove Company.

It opened in 1897 on Paisley Street and in 1929 a brand new plant was built at the corner of York and Victoria Roads.

There is a good chance that if you lived in Guelph during this period, one of your relatives may have worked at the plant. And, if you used a wood burning stove for both heat and for cooking, it just might have been bought from the Guelph Stove Company.

W.C. WOOD COMPANY

Guelph had a global pioneer in the W.C. Wood Company on Arthur Street in the Ward. The plant became a leader in the design and manufacture of home appliances like refrigerators, freezers, dehumidifiers, water heaters, and even agricultural machinery. Opening in 1930, the appliance manufacturer grew quickly in Guelph and across the country. It employed thousands of families here and in plants across North America and grew to become the largest freezer manufacturer in Canada. Like many local students, I worked summers at the plant in the early 1970s and it helped to pay my way through university.

As many companies across Canada were pushed out of business because of the recession in 2008 followed by the economic collapse in the fall of 2009, the W.C. Wood Company was doomed too. A household name for nearly 80 years, its factory doors in Guelph closed forever on Nov. 17, 2009.

A family-oriented business, with dances and picnics, the closing of the W.C. Wood company was the end of an era in Guelph. Today, the Arthur Street South site is home to Metalworks – a high-rise condo and townhouse development.

GUELPH CARPET FACTORY

The Speed River was not only important for mills, but also to produce textiles.

In the mid-1920s, the Guelph Carpet Factory and its affiliate, the Guelph Spinning Mills, was constructed on Arthur Street. By 1952, the Mills were named Harding Carpets and at the time became Guelph’s largest employer with a payroll which often topped 600. Harding Carpets closed in 1978 to make way for a condo development.

Another example of a former mill in the Ward turned into an upscale condo development was Harding Yarns, a division of Harding Carpets.

It was built at 83 Neeve Street in 1904. The building was often called the “Dye House” and the joke going around town was that some immigrants who first came to Guelph would not work there because they thought it was a funeral home. At the time, the expanding and booming tapestry carpet market provided lots of employment for people in Guelph and those who lived in the Ward.

TAYLOR-FORBES

St. Patrick’s Ward boasted other companies and plants too.

Taylor-Forbes, one of Canada’s largest manufacturers of push lawn mowers and general hardware, was founded in 1902. It was located on the former site of Allan’s Mill on the east bank of the Speed River.

The plant also produced a wide variety of other products including hinges, washing machines, boilers, foot scrapers, radiators, and waffle irons. Once again, like other plants in the Ward, Taylor-Forbes grew into one of the largest employers of skilled labour in the city. In 1910, it became the first industry in Guelph to use hydro electric power.

During both World Wars, the company was awarded many large contracts manufacturing shell and metal castings for military vehicles. Taylor-Forbes peaked in size at 500 employees in 1924 but was bankrupt by 1955.

BEAVER LUMBER

The Ward even featured a Beaver Lumber store. The company, once Canada’s leading supplier of lumber and building materials, was founded in 1906. The Guelph division was located at 64 Duke Street. Brewing giant Molson Canadian bought the chain in 1972 and then sold it to Home Hardware in 1999.

FIBERGLAS

Ottavio Dal Bo was one of the first Italian immigrants to work at the Fiberglas plant at 247 York Road, now Owens Corning.

He began working there in the early 1950s until his retirement in 1984. His son, Sebastian, fondly remembers his dad bringing home green allies from the plant so he could play marbles in the neighbourhood. Many of my Italian relatives, cousins, and much later myself, worked at the Fiberglas plant. I worked summers at the plant under lead hands Luigi Di Gravio in the mat department and then in shipping with Bruno Porcellato. They were both well respected, hard working, kind, patient, and wonderful bosses.

From Luigi and Bruno, I learned the importance of coming and being ready to work before your shift even started, giving your best effort, and to always be a team player.

A part of the Guelph community since 1951, Fiberglas became a global pioneer and industry leader in glass fibre reinforcements and over the years employed thousands of workers.

GUELPH PAPER BOX COMPANY

On some weeknights and weekends, myself, and many of my friends from Sacred Heart School use to play a game called British bulldog on the front lawn of another company in the Ward - the Guelph Paper Box Company on Huron Street.

The company employed many workers from the Ward and across the city.

PAGE-HERSEY COMPANY

This company built a large plant on York Road where between 250 to 300 employees produced iron pipes, iron tubing, and later auto parts. The company grew during the two World Wars as the plant produced shell casings for large artillery guns.

Page-Hersey regularly recruited from the local Italian population. Several Italians, as was customary, used their contacts back in Italy to bring relatives and friends over to Guelph to work at the Pipe Factory. Many workers who lived in the Ward not only lived with relatives, but many lived in boarding houses that were within walking distance to a company or plant. In the early 1900s, the Guelph city directory listed 133 Italians living very close to or beside the Page-Hersey plant.

A few years after World War II, business slowed down in Guelph and the company moved its production to other Page-Hersey plants in Ontario.

So many workers who laboured in these plants in Guelph’s early industrial period endured many dangerous and terrible working conditions. As you can imagine in many of these factories, especially in the foundries, working conditions were dusty, dirty, grimy, unsanitary and in many cases hot.

Employment came at a price. It has been reported that in the early 1900s, one accident, (lost fingers, crushed hands, burnt faces), occurred almost every year in some of these plants.

Over time, the ongoing pressures of inflation, recession, and globalization forced most of the plants and foundries in the Ward to shut down. Today, many have been demolished and replaced by high rise housing developments. In the invisible spaces of these once pioneering industries remains memories of an era in the original Ward that will never be forgotten by those who laboured in these plants.

All those in Guelph who laboured in these foundries and factories in the ‘Old’ Ward are heroes. They had no medical coverage, no workman’s compensation, no disability benefits, no sick days, no health care, no stress leave or even air conditioning during the hot summer days and nights.

In these early decades most men and women worked for one company their entire life until retirement. Steady work and having a job gave them a sense of pride, self-respect, and self-satisfaction. Lots of young kids, (some as young as 12), lied about their age to get work so they could help support their families. They new the importance of work.

In the words of Guido Sartor, “Working in these factories in the Ward was a character builder. It gave you respect for work...there are no free rides in life. I learned that hard work will always pay off.”

The industrial landscape of the Ward produced an economy all its own. These companies, factories, and plants provided employment that helped in the growth and prosperity of a legendary neighbourhood in Guelph that will be talked, written about, and remembered for years to come.