It was the summer of 1914 and Guelph was a town of 15,000 people where “everybody knew everybody.”

England had declared war on Germany and hundreds of young Guelph men rushed to enlist.

“We’ll be home by Christmas,” was what many said.

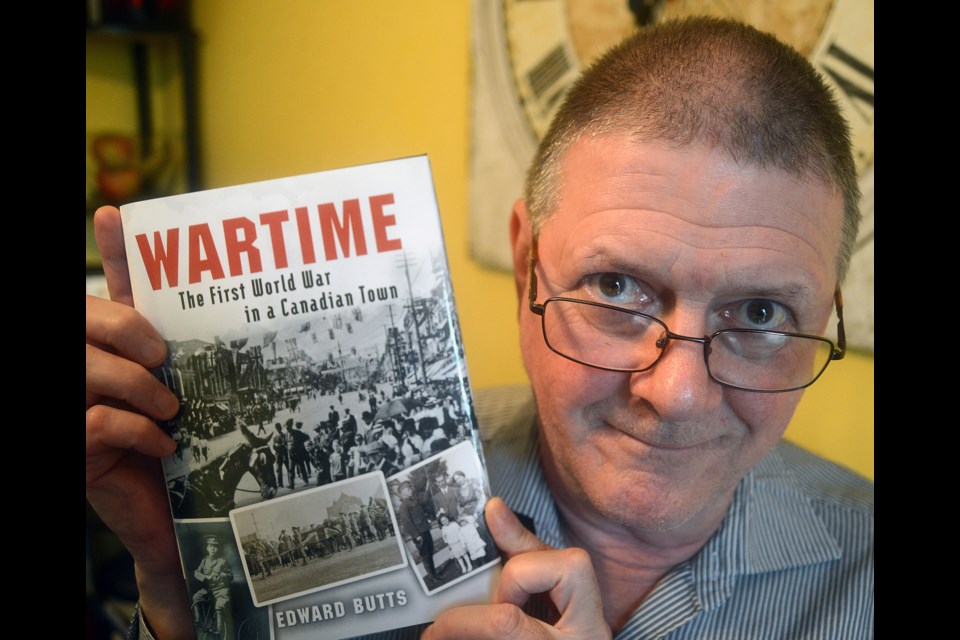

“It was all ‘rah, rah. Up the Empire!’ and everything,” says local author Ed Butts.

It took five years for some of them to return. Many never did. Those that returned earlier came home maimed or sick.

The war not only affected those that went off to fight it, but also those that lived in the town they left behind.

Wartime: The First World War in a Canadian Town, is the latest work by Butts, capturing what happened in Guelph from 1914 to 1919.

“There were lots of homes that had been affected by the war. Either somebody had been killed or somebody had been disabled,” says Butts, the author of over 20 books. “Guelph was a small town and everybody knew everybody.”

In total, 3,300 men from the Guelph area went off to fight in World War I and the names of 216 who died are listed on the cenotaph plaque, although there were a handful of others whose names were left out.

Word of a loved one’s death was usually delivered by the Great Northwest Telegraph Company and it wasn’t uncommon for people who had someone away fighting to refuse to answer their door for fear it was bad news being delivered.

“People dreaded the sight of the telegraph boy on the street,” Butts says. “And if you went to visit someone you wouldn’t knock on their door, you would yell from the stoop instead.”

Wartime: The First World War in a Canadian Town started out as something completely different.

A project conjured up between Butts and Phil Andrews, the editor of the now defunct Guelph Mercury daily newspaper, saw Butts write a series of articles on the people behind the names on the cenotaph plaque honouring those killed in action during World War I.

The book grew out of that.

“When you start researching, it’s no longer just a name on a plaque any more. It’s a person that went here, that walked these streets, that went to GCVI and went to the local church,” Butts says.

Butts says publisher James Lorimer gave the go-ahead for the book, stressing that it focus on the fact that Guelph’s experience during the war was representative of many small Canadian towns back then.

Butts spent hundreds of hours researching at the museum, the Guelph Public Library microfilm, interviewing descendants of war veterans and going through letters mailed home from the front.

The book looks at the patriotic fervor that gripped the nation when war first broke out, then how it waned on the home front once the realities of war began to trickle back home.

Recruiters would shame young men not seen in uniform for abandoning their duties. Women handed out white feathers – a symbol of cowardice.

The book touches on the people that died and how those waiting back home were told of their death. He looks at what happened once they returned, with many wounded ending at the Guelph Reformatory, which was transformed into a place where recovering veterans could learn new trades.

“The constant worry back home was that loved ones weren’t going to come home or were going to come home maimed,” Butts says.

Still, life went on. Not all of it honourable.

Women had to replace men in the workplace, usually at lower pay and under the opinion that they were lesser workers because of their gender.

“People gave up good jobs to go off to war and families left behind often had to move in with relatives,” Butts says.

Fifty people who had previously settled in Guelph from countries the Empire now considered enemies were shipped off to detention camps.

There were shortages. White flour all but disappeared. Wood went to the war effort. Even pencils were scarce.

Guelph’s militia guarded key points, including the gas plant and key bridges. Plots to disrupt the war effort were discovered in other towns.

German-American spy Charles Respa even spent some time in a Guelph jail, hidden from those back in Windsor who might have ideas of springing him from his cell.

Guelph, like many towns, celebrated the war a little early. An armistice was called to stop the fighting on Nov., touching off parades, but the official end of the war came a few weeks later.

“It was more subdued,” Butts says of the victory celebrations.

“It wasn’t as big as an outpouring of patriotism as it was at the beginning of the war. A lot of people had been affected.”

Wartime: The First World War in a Canadian Town is available at The Bookshelf and Indigo.

A reading and discussion of the book is planned for the Guelph Historical Society on Nov. 7 and the Guelph Public Library on Nov. 8.